By Françoise Malby-Anthony, 2019 (336p.)

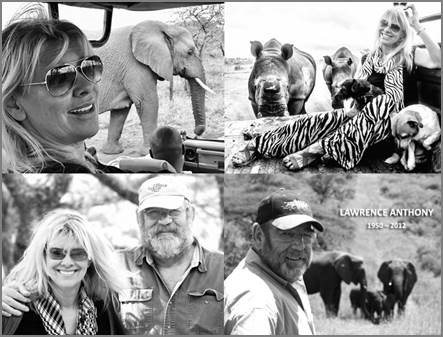

This is a fantastic book by French-born conservationist Françoise Malby-Anthony, who founded the Thula Thula Elephant Safari Lodge (Website), a 5-star resort located in a 4,500 hectare wildlife conservancy in South Africa. Françoise’s husband, Lawrence Anthony (Wikipedia), was a South African-born conservationist and author of The Elephant Whisperer (Amazon). He passed away from a sudden heart attack in 2012, after which she continued their mission of conserving wildlife. As the title suggests, the book is largely about elephants, but it’s also a touching autobiography of a brave and determined woman.

Françoise Malby-Anthony and her deceased husband, Lawrence Anthony.

Françoise Malby-Anthony and her deceased husband, Lawrence Anthony.

Elephants are known more for their memories than their ability to disappear. “You’d think it would be easy to find a herd of elephants,” writes Malby-Anthony, “but it isn’t. Animals big and small instinctively know how to make themselves disappear in the bush, and disappear they did. Trackers on foot, 4×4s and helicopters couldn’t find them.”.. “Nana and Frankie sensed the turmoil and disappeared, hiding the herd in the deepest corner of the reserve until they felt the threat had passed.”

Elephants are also surprisingly compassionate animals. They live as long as humans and are known to mourn the dead for years. Malby-Anthony tells of how they mourned her husband’s passing: “We hadn’t seen them in months. Why now? Why this exact weekend? And why were they so anxious? No science book can explain why our herd came to the house that weekend. But to me, it makes perfect sense. When my husband’s heart stopped, something stirred in theirs, and they crossed the miles and miles of wilderness to mourn with us, to pay their respects, just as they do when one of their own has died.” … “Exactly a year ago, on 4 March 2012, the weekend of Lawrence’s death, the herd had inexplicably come to the house too. It was one of those strange phenomena in the bush that is impossible to explain scientifically but every one of us at Thula Thula knew they had returned because of Lawrence.”

Another amazing elephant trait is their strong sense of community. They roam in groups led by a matriarch, which during most of the book was Nana. Before Nana died of old age, she passed the baton to one of her daughters. As one of the first elephants the couple saved, Nana was dearly missed by both humans and the herd. “Nana was a strict matriarch who wouldn’t tolerate hanky-panky on her watch,” Malby-Anthony explains. “We know elephants have superb memories, so she wouldn’t have forgotten the dark days of her life before she came to us – born in Zimbabwe, sold to a game reserve in South Africa, almost ending up in a Chinese zoo. In my heart, I knew she understood how Lawrence and I had saved her and the herd, and how I continued to fight to protect them. So much water had gone under the bridge since those early days. We had both become matriarchs before our time and taken on responsibilities we never thought would be ours. You adapted quicker than me, I thought ruefully, but I’m getting there.”

Thula Thula has a plush resort on a 4,500 hectare protected property.

Thula Thula has a plush resort on a 4,500 hectare protected property.

The book highlights how elephant and rhino populations are threatened by rampant, illegal poaching, mostly for export to Asia, where they are used for alternative medicinal purposes rooted in superstition. While poaching has seemed unstoppable even with armed guards, drones, and infrared cameras, Malby-Anthony has overseen the use of innovative approaches that are proving effective. “Poaching was decimating rhinos and there was nothing to counter it – until a South African found a way to make horns unsellable and unusable.” … “The woman I spoke to was very enthusiastic about how poisoning horns was the answer to saving Africa’s rhinos. ‘I’m not a scientist so please explain how it works,’ I asked. ‘We inject a cocktail of toxins and indelible dye straight into the horn using special high pressure equipment that forces the infusion to spread through the horn. You can’t see the dye but X-ray machines at airports can pick it up.’ But surely that will poison my rhinos? ‘Not at all. The horn has no direct blood vessel contact with the body so there’s no risk whatsoever for the animal. It’s an absolute breakthrough in protecting them.’ The more poisoned horns we have in South Africa, the safer our rhinos will be.”

All told, this was a pleasant and interesting read. While far from being an investment book, An Elephant in my Kitchen corroborates Thomas Phelps’ principle in his 1972 classic, 100 to 1 in the Stock Market (Victori Review): “Forty-six years ago, when I was paying my way through equatorial Africa by shooting elephants for ivory, I learned this simple principle: When looking for the biggest game, be not tempted to swing at anything small. Elephants’ ears are very keen. Never after firing a single shot at a guinea hen, a colobus monkey, or an antelope, did I see an elephant that day.”

Regards,

![]()

HIGHLIGHTED EXCERPTS:

Chapter 1. The only walls between humans and elephants are the ones we put up ourselves

Not that Lawrence would dream of giving up his beloved Nana, the herd’s original matriarch; theirs was a two-way love affair because Nana had no intention of giving him up either. They met in secret. Lawrence would park his battered Land Rover a good half kilometre away from the herd and wait. Nana would catch his scent in the air, quietly separate from the others and amble towards him through the dense scrubland, trunk high in delighted greeting. He would tell her about his day and she no doubt told him about hers with soft throaty rumbles and trunk-tip touches. What a difference to the distressed creature that had arrived at Thula Thula back in 1999! We had only just bought the game reserve – a beautiful mix of river, savannah and forest sprawled over the rolling hills of Zululand, KwaZulu-Natal, with an abundance of Cape buffalo, hyena, giraffe, zebra, wildebeest and antelope, as well as birds and snakes of every kind, four rhinos, one very shy leopard and three crocodiles.

We struggled to find them. You’d think it would be easy to find a herd of elephants, but it isn’t. Animals big and small instinctively know how to make themselves disappear in the bush, and disappear they did. Trackers on foot, 4 × 4s and helicopters couldn’t find them. Frustrated with doing nothing, I jumped into my little Tazz and hit the dirt roads to look for them, with Penny, our feisty bull terrier, as my assistant.

We hadn’t seen them in months. Why now? Why this exact weekend? And why were they so anxious? No science book can explain why our herd came to the house that weekend. But to me, it makes perfect sense. When my husband’s heart stopped, something stirred in theirs, and they crossed the miles and miles of wilderness to mourn with us, to pay their respects, just as they do when one of their own has died.

Nana was a strict matriarch who wouldn’t tolerate hanky-panky on her watch.

Chapter 2. Falling in love with Thabo

But life’s like that. Sometimes it takes a push to make dreams come true.

Chapter 3: Poaching is war

Chapter 4: Magic money tree

Chapter 5. Reality strikes

herd’s matriarch usually inherits the role from her own mother and she is their teacher, referee, keeper of memories, travel guide and bush stateswoman rolled into one. They turn to her in a crisis, the little ones learn the ways of the wild from her, and she ‘negotiates’ with other herds they might come across. She is their anchor and their rock.

Chapter 6: Enfant terrible

Chapter 7: French temperament

Chapter 8: Baby Thula

Chapter 9: Long live the king

Chapter 10: Dangerous Deals

Chapter 11. Courage is doing what you’re afraid to do

Exactly a year ago, on 4 March 2012, the weekend of Lawrence’s death, the herd had inexplicably come to the house too. It was one of those strange phenomena in the bush that is impossible to explain scientifically but every one of us at Thula Thula knew they had returned because of Lawrence. Elephants mourn their dead for a long time. Years after Mnumzane died, they would return to where his bones lay and linger for hours, dark streaks lining their cheeks from their temporal glands, touching and picking up the bones in an elephant ritual that we didn’t understand. They have a sense of time beyond our comprehension and for me these beautiful, sensitive creatures were doing exactly what we had done two days earlier – marking Lawrence’s death in their own way.

I understood then that it wasn’t about me, it was about them. Lawrence’s ashes had long since been absorbed by the earth at Mkhulu Dam and the herd had nothing physical to touch and revere. I believe they returned to where Lawrence had lived simply to be in the same space they had once shared with him. No one had forgotten him, especially not them, and whenever I felt anxious or overwhelmed in the months that followed, I drew such strength from that visit. They needed me but I also needed them.

Chapter 12. Ubuntu

The herd was on the verge of being shot and look what happened – you and Lawrence came into their lives and they were given a second chance. That’s hope, Françoise. Never forget that. There’s always hope.’

‘Here’s to another matriarch, Lawrence’s mum, who even in her nineties keeps the Anthony clan together. Our Nana really did live up to his hopes that she would be as wise and strong a leader as his mother.’

Chapter 13. Stars are brighter in Africa

The first time I wrote about my dream of opening a rhino sanctuary was in a newsletter in August 2013.

‘It would be incredible if they said yes,’ Alyson sighed, then shifted forward in her chair. ‘Right. Back to work. Dreaming will get us nowhere.’‘Dreaming will get us everywhere,’ I said softly, walking over to the window.

Chapter 14. How do I keep you safe?

South Africans are amazingly inventive people, especially when they have their backs to the wall. Lock them in a cage and they’re guaranteed to find an ingenious way out. Poaching was decimating rhinos and there was nothing to counter it – until a South African found a way to make horns unsellable and unusable. I thought the idea was brilliant and I immediately tracked down an organization with experience in the procedure. The woman I spoke to was very enthusiastic about how poisoning horns was the answer to saving Africa’s rhinos. ‘I’m not a scientist so please explain how it works,’ I asked. ‘We inject a cocktail of toxins and indelible dye straight into the horn using special high pressure equipment that forces the infusion to spread through the horn. You can’t see the dye but X-ray machines at airports can pick it up.’‘But surely that will poison my rhinos?’‘Not at all. The horn has no direct blood vessel contact with the body so there’s no risk whatsoever for the animal. It’s an absolute breakthrough in protecting them. The more poisoned horns we have in South Africa, the safer our rhinos will be.’‘But how can it be legal to poison something that we know people might eat? I don’t want anyone’s death on my conscience, no matter how much I hate that they buy rhino horn.’‘It won’t kill them, but believe me, it’ll make them very sick. No one is going to want our horns! Imagine how fantastic that would be.’ It sounded too good to be true, and very expensive. ‘It’s about the same price as dehorning, and included in the price is the dye, micro-chipping the horns and we take a DNA sample for the national rhino database.’‘You’re a good saleswoman,’ I laughed. ‘I believe it’s the only thing that will save rhinos. Everything else that’s out there hasn’t helped. This will.’ Her company’s solution certainly had a lot going for it, although it still carried the risk of having to anaesthetize the rhino. ‘Have you ever had a procedure go wrong?’ I asked. She seemed to hesitate for a moment. ‘It didn’t really go wrong, because there are always risks with immobilizing large mammals. Put it this way, we’ve had a less than two per cent mortality rate since we’ve been doing this.’

I reluctantly watched him screw a long probe into the hole, then he switched on the high-pressure pump and bright-blue infusion entered the horn. I hated every minute of it. I knew it had to be done but it was gut-wrenching to see her surrounded by cold metal – 4×4s, infusion equipment, wires, probe – and with men crouched at her head wearing long black gloves to protect themselves against the toxic liquid they were injecting into her. It felt more like dramatic head surgery than a simple thirty-minute procedure.

I’m sorry we have to do this, but I don’t know how else to keep you safe. I will never stop protecting you, I promised silently.

Mike shifted his attention to Thabo and once he had successfully poisoned his horn too, and both rhinos were back on their feet, he packed away his tools and medical kit and looked at me. ‘I’ve got some good news for you,’ he smiled. ‘I found a solution to control the elephant population.’‘Really? No culling?’ I asked. ‘We’re going to put the bulls on the pill!’‘That makes a nice change,’ I grinned. ‘For once, males will be responsible for birth control.’ He outlined his strategy to me. Twice a year, the older bulls would be darted with a special contraceptive formula that would not only control their fertility but would also help manage their periods of being in musth, when their behaviour becomes aggressive and unpredictable. The method was affordable, available and reversible. ‘How does it work?’‘That’s the beauty of it. It’s steroid based so we’re not injecting them with hormones, which means there’s no risk of making them more aggressive or changing their behaviour in a long-term way.’‘No risks at all, are you sure?’‘Absolutely. If you don’t count the bulls being irritated by the helicopter when we’re darting them.’‘How soon can you do it?’‘We’ll need to apply for permission but that shouldn’t take long. Quite frankly, I think the authorities will be delighted for us to try this out.’ I felt like throwing my arms around the man. He had handed me a much-needed reprieve from the wildlife authorities. Things were looking up.

Chapter 15: Never Give Up

Chapter 16: An elephant in my kitchen

Chapter 17. Follow your dreams, they know the way

We unofficially opened the doors to our orphanage at the end of 2014, almost a year to the day after receiving funding from Four Paws.

Chapter 18: Ellie

Chapter 19: And then there were seven

Chapter 20. Silent killers

Snares are the silent killers of the bush. All it takes is some wire and a slip-knot. The poacher strings up a noose where an animal is likely to pass – usually hanging at head level from a tree – and as soon as an unsuspecting neck or trunk passes through the loop, it pulls closed. The more the creature struggles, the more the snare tightens. Death is slow and cruel, and the animal rarely escapes. They may be able to yank the snare free from what it’s attached to, but that only makes it worse because the animal goes into hiding and we have less chance of finding it to help it. Thank heavens this calf had managed to stay with the herd. Snares are cheap, easy to set up and dreadfully effective. The first thing our anti-poaching unit does every morning is scour the reserve for them. We’ve gone through periods when they dismantled up to ten snares a day. Lawrence and I always used to say that you can’t interfere with nature, but sometimes you have to, especially when an animal is injured because of humans – as with snares.

A giraffe’s neck is immensely powerful – as I learned from Lawrence on my first visit – and once the animal is able to lift its head, it very quickly gains the momentum to stand and can be back on its feet within seconds: a potentially lethal situation in the middle of a snare-removal procedure.

Poachers killing for food typically break in through our perimeter barrier at night, string up a whole lot of snares and slip out again. A few days later, they’re back to pick up the animals they’ve trapped. Once they’ve taken as many as they can carry, they disappear again without bothering to disable the remaining snares. Any captured animal they leave behind dies a slow death. Where is their conscience? The cruelty destroys me.

There are two types of poachers – those killing for the pot and those killing for profit. The latter type is hell-bent on money and doesn’t give a damn about animals or endangered species, and he won’t hesitate to shoot the men and women who risk their lives to protect them. His focus is financial gain and he knows he’ll be well paid for practically every part of the animal – skin, horns, tusks and meat. And he’ll get an even higher price if the body parts are bought for the more sinister, bad muthi, the dark side of traditional medicine.

Lawrence would have been right there in the thick of things. Nothing frightened him, especially not if one of his beloved elephants needed help. I didn’t have his gung-ho fearlessness to join in, and to be honest, I found it too hard emotionally. I was terrified. What if the baby hadn’t survived the night? What if something went wrong with the procedure? I don’t have nerves of steel.

It’s awful to use a helicopter to force the elephants to scatter but it’s the only way to safely reach an animal needing medical care. The vet took aim and darted the calf with a sedative. Within seconds, the medicine kicked in and the calf sank to the ground.

That day, in our long- standing tradition of naming baby elephants after the person who helped save them, I christened the calf Vusi, and I was so proud of the team that I put a few bottles of champagne on ice and invited everyone for celebratory drinks at 6.30 that evening at the lodge. What could have been a really tough rescue operation had gone so smoothly that it had taken less than half an hour. That was partly thanks to Mike Toft and my courageous rangers but also thanks to the beautiful faith the herd had in us. I felt so honoured that they had entrusted their injured baby to us. Everyone, humans and elephants, had worked together to save him. My house on Thula Thula is about two kilometres from where we were having the champagne celebration so I only left at 6.25 p.m. to go there. Who should be at the entrance of the lodge to meet me? The entire herd! I couldn’t believe my eyes. When elephants go through such trauma – helicopter, panic stampeding, forced to abandon their calf – they can disappear for weeks on end. Not this time. They were all there, every single one of them, and they stayed with us for hours, so serene, moving silently along the lodge fence. Who knows for sure what they were thinking? But they were looking at us and glowing with warmth and love. There was no doubt in my mind that they had come to say thank you.

Chapter 21: Only when the well dries do we know the value of water

Chapter 22. Rather a live rhino without a horn than a dead rhino without one

There’s only one reason a drone flies over Thula Thula and that’s to locate our rhinos. ‘Do we know where Thabo and Ntombi are?’ I asked quietly. ‘Richard is with them. He’s armed and prepped for trouble. I’ve called backup.’‘Good. And the drone?’‘We’ll shoot the damn thing.’

Chapter 23 The hippo who hated water (link)

Chapter 24. Love in the bush

Frankie and Gobisa were standing slightly apart from the rest of the herd, trunks intertwined and foreheads touching as if sharing secrets. I love seeing them together. It’s a lonely job being matriarch and I’m so happy for her that she has Gobisa as a mate.

Rain in our Zululand paradise is often regarded by locals as a blessing.

Chapter 25. Nowhere is safe

‘How can I help?’ she asked. ‘Shall I start a crowdfunding campaign? What do you need?’‘We’ve bolstered security but we need more, and we need urgent protection for the rest of the reserve to make sure poachers don’t get in again.’‘I’ll start with a goal of $6,300,’ she promised. She reached her target in five hours. Donations flooded in from all over the world. People were appalled and wanted to help. The outpouring of love and concern was incredible. There was so much goodwill. A Mozambican farmer walked to us to bring his donation. So much goodness shone over us. Donations sky-rocketed and within twenty-four hours over $30,000 had flowed in and continued to come in until $56,800 was raised.

Nana and Frankie sensed the turmoil and disappeared, hiding the herd in the deepest corner of the reserve until they felt the threat had passed.

In the middle of this chaos, a four-year-old white rhino was slaughtered in a Parisian zoo, the first rhino poaching in Europe. It almost broke me. Nowhere was safe. Nowhere. If rhinos weren’t safe in zoos, how would they ever be safe in the wild?

I don’t believe in the clichéd platitude that everything happens for a reason but I believe with all my heart that, when tragedy hits, we have to find a way to give it reason. To do our best to let good come out of it.

The orphanage perimeter fence was repaired and connected to a high-tech alarm unit. Motion detector beams now pick up the slightest movement. There are infrared night-vision cameras throughout the reserve that track activity and feed information into a cloud-based portal. If a poacher disables a camera, an alarm goes off both on-site and in an external control room. Television screens with surveillance feeds were moved from the orphanage to the off-site control room.

Fighting for what I believe in is what gets me out of bed each morning.

Chapter 26. Keeping the dream alive

Our other crucial partner was Four Paws. Heli Dungler had seen for himself how destructive the human politics had become, but he too stayed committed to keeping the orphanage open, and to my great relief he didn’t hesitate to renew his foundation’s financial collaboration. ‘We’ve been thinking about creating a sanctuary for ex-circus elephants,’ he said to me recently. ‘Maybe this is the moment to explore taking the orphanage to a different level.’‘That’s a wonderful idea,’ I replied quietly. ‘It fits perfectly with what we do at Thula Thula.’‘It’s probably only feasible in a year or two’s time, so in the meantime we’ll help you keep the facility open for other wildlife needing help.’ By mid July 2017, a new joint venture agreement was signed with Four Paws and the local amakhosi. We were officially partners again and thrilled to be up and running. Since we were turning a page and broadening our focus, we changed the name to Thula Thula Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre.

Chapter 27. Frankie vs Frankie

Elephants are never in a hurry, whether they’re going somewhere or having a meal. I’ve never in my life seen an elephant gulp down food quickly.

We know elephants have superb memories, so she wouldn’t have forgotten the dark days of her life before she came to us – born in Zimbabwe, sold to a game reserve in South Africa, almost ending up in a Chinese zoo. In my heart, I knew she understood how Lawrence and I had saved her and the herd, and how I continued to fight to protect them. So much water had gone under the bridge since those early days. We had both become matriarchs before our time and taken on responsibilities we never thought would be ours. You adapted quicker than me, I thought ruefully, but I’m getting there.

The trunk is one of the most delicate and sensitive parts of an elephant and her pain must have been mind-blowing.

It’s such a reminder about life itself. We can never know what’s around the corner and it makes it all the more urgent to relish precious moments of peace when they come our way.

Every available 4×4 and ranger was out looking for Susanna the next day. It always astonishes me when we can’t find the herd. Twenty-nine is a lot of elephants to go missing, but I’ve learned with them – if they don’t want to be found, they won’t be.

Afterword (March 2, 2018)

Our herd has grown to twenty-nine elephants and counting.

We are turning Lawrence’s vision of creating a huge conservation area into a growing, sustainable legacy for generations to come, and there are already two expansion projects on the horizon. The first is with private neighbours for an additional 1,500 hectares, which will tick the box for the wildlife authorities in terms of our land-to-elephant ratio and give us enough space to bring in lions, making us a big five reserve at last.

As I celebrate thirty years in South Africa, I have learned never to give up, to hold on to my dreams, always to search for a silver lining, and that by looking forward, the difficulties of the past eventually fade out of sight. Thula Thula is, and always will be, my home. Françoise Malby-Anthony Thula Thula, South Africa

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY: https://www.ideacity.ca/speaker/francoise-malby-anthony/

As the head of the Thula Thula game reserve that she and her husband founded over 15 years ago outside Durban, Francoise Malby Anthony has made it clear that she intends to continue the work that the two of them started. Their efforts haven’t gone unnoticed, by either the international community, or the creatures that they worked so hard to shelter. Today, she’s actively involved in the ongoing battle to protect rhinoceroses, which are routinely hunted and killed for their horns. Her latest step in their conservation program is the infusion of rhino horns with a special ink, which acts as both a deterrent to and a means of identifying poachers, should they try to move the horns across borders. Through her continued involvement with the Lawrence Anthony Earth Organization, and her ongoing work running the Thula Thula game reserve, Francoise is at the forefront of the battle for both our planet, and the many species that call it home.