By Tamim Ansary, 2019 (448p.)

This was an excellent book because it exposed the greater cycles in human history that are typically not so well presented and organized by other historians. Ansary knows how to connect the dots through the ages. One of my many precious takeaways from his long lookback was that when civilizations were well into decline, they had no idea that it was happening. Instead of alarmed by signs of ruin, they thought instead that they were reaching a pinnacle of greatness. Ansary gives the example of the Qing civilization, which was the biggest that China ever had. “With the Qing in power, there was still no way to know that China was on its way down. … In 1700, China still had every reason to see itself as the supreme central power on Earth.”

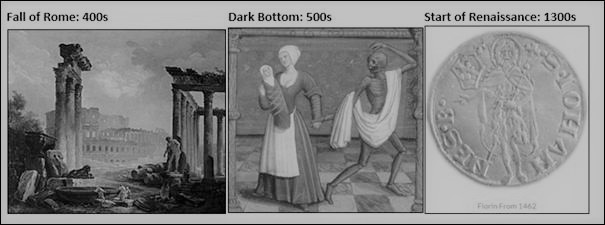

As a side-note, many (if not all) great civilizations have ultimately gone down a similar path of decay, so it’s not hard for a pessimist to wonder when the Great American Empire will take its turn. Ansary raises this question towards the end of his book, and so did historian Niall Ferguson in the August 21, 2021 issue of The Economist (link). The way I see it with my investor lens, regardless of whether it’s up or down from here for America (my personal call is up), it would be no good reason to sell America short – if only because the timing of these things are unknowable, and decline periods can extend for centuries. In The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age (2008), John Greer estimates that it takes, on average, about 250 years for civilizations to decline and fall. I am suspicious of Greer’s estimate and some other things about him, but Ansary’s book does seem to throw around centuries as if they were fortnights. Rome’s decline, for example, is thought to have started around 200 AD, when the empire was being attacked by Germanic tribes. But the city of Rome would only fall to Germanic rule after it was plundered by the Vandals (Wikipedia) over two-hundred years later. Vandalism got its bad reputation after they helped trigger the Dark Ages. Europe’s population declined during this brutal period, with headcount hitting bottom a full century after the ultimate fall of Rome. Then it took another seven centuries (yes, seven), for the Renaissance to arrive in Florence, and the Florin to gain wide circulation. Only then came the Medicis (Wikipedia) and the Fuggers (Wikipedia). Another one hundred years later, we got Tulip Mania, which Charles Mackay famously described in Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841). It was in the preface of that book that Mackay wrote his famous quote: “Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

Intrigued by John Greer’s quote, which I got from this article, I did some digging and discovered Greer is a residing officer of the Ancient Order of Druids in America (AODA). Founded in 1912 as a branch of the Ancient and Archaeological Order of Druids, which is registered in the U.S. as a 501(c)3 religious non-profit organization, one must be 18 or older and wish to follow a personal path of nature spirituality rooted in their local ecosystem to become a member. It costs only $50 and can be paid with PayPal, but how ancient can such an order be? According to its Wikipedia page, it was founded in Britain in 1781 in the King’s Arms Tavern near Oxford. That’s not really an ancient order, but the Druids themselves were indeed an ancient society that lived among Celtic tribes in Gaul (modern France). The only detailed description of the Druids comes from Julius Caesar’s book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico (50s BCE). Caesar wrote in admiration that they were one of the two most important social groups in the region, and that it could take decades to complete their course of study. Tragically, not one ancient text by the Druids survived. When the Romans invaded Gaul in the 1st Century BCE, it took the Druids 100 years to get wiped out, and largely forgotten. Then it was only in the 18th and 19th centuries that fraternal groups were founded in Victorian England based on ideas about the ancient Druids. These groups were secretive and extremely superstitious. They also had a bad reputation because the Druids were said to be avid practitioners of human sacrifice. Aside from formalities, though, the order that John Greer belongs to sounds more like environmentalism than a radical religion. Ansary never mentions the Druids in his book, but he does mention other civilizations that were largely forgotten, and it was because of his insights that I embarked on this tangent. ?

Suspect author, John Greer (Amazon picture)

Suspect author, John Greer (Amazon picture)

Before exiting the Druid tangent, I googled King’s Arms Tavern near Oxford Street in Google Maps and there were dozens of hits – as I would have expected, since there seems to be a King’s Arm pub in every corner of London. But there is a special King’s Arms tavern in Oxford that has its own Wikipedia page. Owned by Wadham College, it is one of the main student pubs in Oxford, as well as the city’s oldest pub. Local myth has it that “the King’s Arm has the highest IQ per square foot of any pub or bar in the world.” The name refers to King James I (reigned 1603–1625), who was involved with the founding of Wadham College in 1607. The site was originally occupied by buildings erected by Augustinian friars in 1268, but after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1540, the land passed to the City of Oxford. Until 1973, the pub’s back bar, known as The Don’s Bar, was not open to women, the last such bar in Oxford. …now that’s not cool.

So back to Ansary, he was born in 1948 and raised in Afghanistan. He moved to the U.S. as a high school student in 1964. He is a prolific writer and speaker, and has delivered many talks on Islam and Middle Eastern cultures. He lives in San Francisco with his wife, two daughters, and a cat. I recall well the open letter he wrote two days after the September 2001 attacks (link to letter). It was widely disseminated at the time (via email), and I remember keeping a printout in my files (back when that’s the way it was done). Those files were recently destroyed by flooding in our basement as a result of hurricane Ike. Anyway, Ansary’s ending statement in that 20-year old letter was prophetic: “…in the end the West would win, whatever that would mean, but the war would last for years and millions would die, not just theirs but ours. Who has the belly for that? Bin Laden does. Anyone else?” Today we see that Ansary was right that it was a mistake for the U.S to invade Afghanistan. Bin Laden himself would only be killed ten years later.

One of the more sobering takeaways from Ansary’s book is that “slavery has existed since there were people to enslave.” He writes: “The Romans built an empire on it, and the Rus got rich selling Slavs to Muslims. Throughout most of history, codes of virtue governing how people ought to treat one another usually only applied to members of the group in question. Such codes kept the inner world in order but didn’t apply to dealings with the outside. The codes saw nothing wrong with enslaving the other.” Its hard to read a book like this and not conclude that the human condition has improved dramatically. I get it that there is still slavery in many places and under different guises, but it’s nothing like it used to be, and the U.S. experience with it is hardly a fluke.

Another takeaway is that history is more inter-related than most texts would have you think. Like the COVID virus, Ansary says that the Boston Tea Party in 1773 and the Declaration of Independence in 1776, started in China. “Yes, the policies of China’s Qing government did contribute to the birth of the United States,” he concludes. The story there is that in 1698 the British government gave the East India Company a monopoly on the importation of tea from China. This same tea became popular in the British colonies, but the colonies were forced by British law to import their Chinese tea from England at a marked-up price. Much as happens in commerce all the time, Americans wanted to bypass a freeloading middle man – and that is the real reason it declared independence.

Ansary also offers precious insights and observations on the history of money. He explains that “money is not, in fact, an invention. Like language, it’s a spontaneous by-product of human interaction. Money is also not a thing; it’s an abstraction. No one trades a cow for a coin because they want the coin. They trade the cow for a coin so they can trade the coin for a wagon. Money is just a way of translating cow to wagon. It brings value into existence as a substance separate from all material things that have value, in the same way that mathematical marks bring quantity into existence as an element separate from all things quantified. … Money emerges in any community where trade exists—which is every community. … Ultimately, for money to work in tandem with taxation, it had to be backed by military might. … paper money requires a central government with complete jurisdiction over economic activity.” As a side note here, it is this observation that government and taxation and paper money are one and the same, that makes me skeptical that bitcoin will ever become a real currency – or at least not in its current form – because it lacks government backing.

Another insight from the book relates to the role of catastrophes in human history. “At least five times in our 5 billion years,” he reminds us, “some catastrophic event wiped out most of the species then alive.” While any wide scale catastrophe is no fun for those who live through it, Ansary claims that it’s not all bad that comes from it. “The Black Death killed a lot of people but for many of the survivors, life actually improved. For one thing, unlike a military invasion, an epidemic doesn’t damage infrastructure: it kills people but leaves roads, buildings, canals, and such intact. And the loss of people has consequences. Before the Black Death, feudal lords were ramping up their use of wage laborers instead of serfs as a way to save money. But after the Black Death—guess what? Lords found themselves facing a labor shortage. With one-third (or more!) of the continent’s population gone, paid workers had unprecedented bargaining power. In the aftermath of the epidemic, wages went up, and peasants hit the roads in search of better opportunities.”

Ansary’s observations are not all rosy. On the environment, he writes: “Hippos, tigers, blue whales, sea otters, snow leopards, gorillas, giant pandas—get ready to say good-bye: all of them are on their way out.” He also claims that the environmental calamity could lead to the next extinction of life on earth. He warns of the polarization of opposing ideologies, and of the cult of singularity, which he dismisses as an elitist ideology that exacerbates inequality. “I myself am not a convert,” he emphatically claims. “The singularity cult cheerfully assumes that when the artificial superintelligence comes into being, it’s whole purpose will be to serve the needs of humans. They picture themselves as immortal children, laughing, playing, eating, lolling. The way it looks to me, however, if the singularity were to happen today, only the rich would live forever. The poor would straggle on in diminishing numbers, surviving for a while because the immortal rich will want servants but become dispensable once technology has progressed far enough to make robots indistinguishable from humans emotionally, sensually, and sexually.” This is similar to the thesis Tyler Cowen put forth in Average is Over (2013). It is also the reason that as a long-term investor and a fund manager, I believe in owning only the few companies that can defy the averages and achieve exponential dominance in the stock market. This is the essence of Pareto’s Law, and is behind the exponential phenomenon I discuss in my book, The Outstanding Factor (2021).

So in closing, The Invention of Yesterday is a gem of a book, and unlike John Greer, Tamim Ansary is an impressive author. It is hard not to get inspired by his writings and by how he manages to connect seemingly unconnectable events throughout human history. When we find ourselves caught up in a narrow frame about the world’s troubles, this is the book to go to. If anything, Ansary helps us recognize that while life is finite, life on earth is an infinite game. The book turns out to offer an abundance of investment lessons, which is probably why I liked it so much. One of the deepest of these lessons is covered in the final chapter, where he concludes: “The danger always seems particularly sharp ‘right now’. I personally don’t remember a time when humanity wasn’t seemingly handcuffed to a runaway train that had lost its brakes and was barreling toward an edge.” I have been known to repeat something similar about the markets: I don’t know of a single point in the past when people weren’t scared of the future for stocks, and yet, they have been rising for centuries.

Regards,

Adriano

Other Books by Ansary:

- Road Trips: Becoming an American in the vapor trail of The Sixties (2016): Road Trips chronicles three journeys the author took between 1969 and 1976, each of which began and ended in Portland, Oregon. Ansary had only recently arrived from Afghanistan where he was born and grew up. In America, he dropped out of a society he had never been part of in the first place, to join a counterculture building a world that would soon replace civilization as it was known; or so they thought. Set against the backdrop of the Sixties turning into the Seventies, this is the story of a collective dream from which the dreamers all woke up alone.

- Games Without Rules: The Often-Interrupted History of Afghanistan (2012): Ansary draws on his Afghan background, Muslim roots, and Western and Afghan sources to explain history from the inside out, and to illuminate the long, internal struggle that the outside world has never fully understood.

- Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (2010): tells the rich story of world history as it looks from a new perspective: with the evolution of the Muslim community at the center. His story moves from the lifetime of Mohammed through a succession of far-flung empires, to the tangle of modern conflicts that culminated in the events of 9/11.

- West of Kabul, East of New York: An Afghan American Story (2003): an urgent communiqué by an American with “an Afghan soul still inside me,” who has lived in the very different worlds of Islam and the secular West.” The book is a personal account of the struggle to reconcile two great civilizations and to find some point in the imagination where they might meet.

Highlighted Passages:

CHAPTER 6 Money, Math, Messaging, Management, and Might

Unfortunately for Smith’s theory, no society has ever been found that operated on barter in the way that he described, for money is not, in fact, an invention. Like language, it’s a spontaneous by-product of human interaction. Money is also not a thing; it’s an abstraction. No one trades a cow for a coin because they want the coin. They trade the cow for a coin so they can trade the coin for a wagon. Money is just a way of translating cow to wagon. It brings value into existence as a substance separate from all material things that have value, in the same way that mathematical marks bring quantity into existence as an element separate from all things quantified. Within a human group, when everything can be quantified in terms of a single unit of measurement, any sort of thing can be exchanged for any other sort of thing. If messaging can be compared to the nervous system of a social organism, money can be compared to its circulatory system: it creates a network of links through which value can flow from place to place. A material good available in one place can pop up as a completely different material good in another place; only money can make this happen. Money emerges in any community where trade exists—which is every community. In prisons, where people generally don’t have cash, cigarettes spontaneously turn into currency. Their value as smokeable items gives way to their value as a precise means of measuring what anything is worth compared to anything else.

Money could not have come into existence without mathematics, which emerged in tandem with written scripts, out of the exigencies of messaging, in a world mediated by long-distance trade, which involved interactions of mutual benefit among people in disparate places—which is a long of way of saying that, in the social universe, everything is connected to everything.

CHAPTER 7 Mega Empires Take the Stage

Ultimately, for money to work in tandem with taxation, it had to be backed by military might.

CHAPTER 9 When Worlds Overlap

Around 29 CE (perhaps a bit earlier, perhaps a bit later), a man named Jesus, son of a carpenter, met John and accepted baptism. Jesus proved to be one of the most charismatic of the possible messiahs in the Jewish nationalist movement. As a result, the local Roman officials arrested him and asked him just one question: “Are you the messiah?” To the Roman officials, that question meant: “Are you leading a rebellion against Rome?” When Jesus said yes, the Roman authorities had him crucified because that’s what Rome did to rebels. Nothing personal, just policy: thousands of rebels had been crucified before Jesus, and thousands more would be crucified after him. Most Romans had no idea Jesus had ever lived much less that he’d died. But Jesus had a handful of followers, some of whom, after his crucifixion, began to murmur that he wasn’t dead. They said they’d caught glimpses of him here and there, alive as you or me. With these reports, the followers of Jesus began proliferating, and this Jesus movement soon diverged from mainstream Judaism.

CHAPTER 10 World Historical Monads

The Chinese had gunpowder; now they started using it in cannons, not just fireworks. In this period, the Chinese invented the magnetic compass. They also invented playing cards, and Song bureaucrats found another novel use for paper—as money. Nowhere else could this have happened, for paper money required a central government with complete jurisdiction over economic activity, and only China had such a system at that time.

PART III The Table Tilts

CHAPTER 12 Europe on the Rise

The money-exchanging business required calculating the value of one coin versus another: How many of this duke’s coin equaled how many of that duke’s? And how much of either coin was worth how much gold? Amateurs could lose their shirts trying to make such calculations. Venetian goldsmiths, however, handled transactions of this type routinely, so they developed the relevant expertise. They set up benches outside their shops to do business. The Italian word for bench is banque, so these guys were called banquers. Today, we call them bankers.

CHAPTER 13 The Nomads’ Last Roar

History was no stranger to plagues. Disease had changed the course of history many times. And it wasn’t always the bubonic plague. The biblical plagues might have been typhus. Malaria probably helped weaken Rome. The plague that ravaged Justinian’s Byzantium might have been smallpox. An epidemic of some never really identified disease seems to have cleared the way for the Islamic expansion of the seventh century. But the Black Death of Europe was the most devastating and consequential flood of disease the world had seen—up to that point. And it happened because the Mongols had produced such a spike in Eurasian interconnectedness. At the time, however, it’s safe to say that no one in Europe made a connection between the Mongols and the plague. The Black Death killed a lot of people but for many of the survivors, life actually improved. For one thing, unlike a military invasion, an epidemic doesn’t damage infrastructure: it kills people but leaves roads, buildings, canals, and such intact. And the loss of people has consequences. Before the Black Death, feudal lords were ramping up their use of wage laborers instead of serfs as a way to save money. But after the Black Death—guess what? Lords found themselves facing a labor shortage. With one-third (or more!) of the continent’s population gone, paid workers had unprecedented bargaining power. In the aftermath of the epidemic, wages went up, and peasants hit the roads in search of better opportunities. This sort of mobility had been illegal in Europe since the days of Roman emperor Diocletian, but now, lords were powerless to stop it.

PART IV History’s Hinge

CHAPTER 18 Chain Reactions

But as family companies came and went, another kind of company began to germinate as well: partnerships among strangers, known as joint stock companies. A bunch of merchants would get together and pool their resources to fund an enterprise more ambitious than any of them could have undertaken alone. They’d outfit a ship and send it to Asia to buy trade goods. Once it came back and the cargo was sold, each merchant got a share of the profits proportional to the amount he’d put in. The share each partner put in was recorded in a document called a stock certificate, hence the term joint stock company. The first of these were usually organized around particular projects. Once the project came to fruition, the partners went their separate ways, in pursuit of other opportunities. Gradually, however, companies of this sort congealed into stable entities that undertook continuous streams of ventures: a new kind of social constellation, which had, in the social universe, some of the same properties that biological organisms have in the physical universe. A joint stock company was held together by one goal—to make a profit. This fit right in with the progress narrative, which conferred ultimate meaning and purpose upon doing better every day, gaining ground, having more. Owning land didn’t align with that narrative quite as nicely, for land stays the same size. A lord might improve his use of what he had, but eventually he reached a ceiling beyond which no further productivity could be squeezed out of his holdings, and if he wanted progress, he had to take someone else’s land. Profit was different. Profit had no ceiling. A company could gain more profit by growing in size, expanding its reach, sending out more ships, going further, bringing back more, selling to a wider base, expanding what it bought and sold. With this sort of improvement and expansion, tomorrow could always, theoretically, be better than today.

In 1600, for normal everyday commerce, Europeans still used coins as currency. But there were lots of locally struck coins floating about. In any given locale, people could use any of them that anyone would accept. A given person might be carrying a few pieces of eight, several English shillings, a bagful of Spanish doubloons. The terrain in which these coins worked was not circumscribed by strict borders because such borders didn’t exist. The money wasn’t mathematically exact, either. Exchanges had to rest on estimates of value. Even when coins were made of silver, their value could only be approximated because people sometimes shaved the rims and melted what they scavenged to keep for themselves. Some coin-issuing authorities—princes, dukes, kings, whatever—mixed baser metals into their coins to stretch their supply of silver or of whatever metal they were purporting to use. How was anyone to tell what a coin was “really” worth? Yes, there were tests one could run, but who had the time for tests in the course of daily commerce? Commercial exchanges were negotiations about the coins used as well as about the products changing hands. The Dutch were the first to figure out a fix. In 1609, the city fathers of Amsterdam chartered a group of private bankers to form a single central bank. Anyone wishing to do business in Amsterdam had to take their money to this bank and open an account. The bank officials decided how much the various coins and whatnot were worth. They put these in a vault and issued banknotes clearly marked with numbers that added up to the amount of value deposited. Within Amsterdam-controlled territory, not only did everyone have to accept those notes as money but no one was allowed to do business using anything but those notes. Banknotes had an absolute value unrelated to the worth of the paper or the quality of the printing. An old, frayed ten-guilder note was worth exactly the same as a crisp, new ten-guilder note. Ten such notes were exactly equivalent to a single hundred-guilder note, no matter what shape they all were in. Banknotes removed money from the uncertainties of the material realm and rendered it purely mathematical. Within the Netherlands, the Bank of Amsterdam soon became the source of a standardized state currency that worked in all territory under Dutch jurisdiction.

CHAPTER 19 After Columbus: The World

Slavery as such was nothing new. People started enslaving people as soon as there were people to enslave. The Romans built an empire on it. The Rus got rich selling Slavs to Muslims. Throughout most of history, codes of virtue governing how people ought to treat one another usually only applied to members of the group in question. Such codes kept the inner world in order but didn’t apply to dealings with the outside. The codes saw nothing wrong with enslaving the other.

The group winning every battle on every front didn’t see their conflicts with the natives as war. War was something civilized people did with other civilized people. They saw it in the same light as battling wild animals in a wilderness.

The trade was going to happen no matter what, for there was money to be made, but anyone making that money needed to feel that capturing humans and working them to death didn’t necessarily mean they were bad people. How could these be part of the same conceptual constellation? Racism provided the bridge. The race-based slave trade was the minotaur chained in the basement of the European colonization of the Americas. The people feasting upstairs did their best to ignore its muffled roars and go on with their dinner.

CHAPTER 20 The Center Does Not Hold

With the Qing in power, there was still no way to know that China was on its way down. Over the next forty years, the Qing brought the whole empire under their governance and extended Chinese power deep into Central Asia. Qing China was the biggest China ever. The Great Wall no longer marked China’s

The Japanese had exploited their island isolation to build a feudal society in which rice held a sacred place and fishing provided the bulk of people’s nourishment. Officially, a fifteen-hundred-year-old imperial dynasty ruled the islands. Daily government was in the hands of tough feudal lords called shoguns, who fielded armies spearheaded by samurai, warriors with a complex cultural tradition that had the qualities of a quasi-religion—analogous to the ghazis, the mystical warrior brotherhoods of the Ottoman state and to the military religious orders fielded by the Catholic Church during the Crusades.

In 1700, China still had every reason to see itself as the supreme central power on Earth.

The Qing and their advisers didn’t particularly like this new world. They liked the cash the Europeans brought, but not their seemingly corrosive culture. They barred Europeans from setting foot in the empire proper, restricting them to a few specified trading posts along the coast. The European traders were to wait there until Chinese merchants came to take their orders. They were to pay their money and cool their heels until their purchases were brought to them. Then, they were to go away. At these haughty conditions, the European traders merely shrugged. They were here to make money, not friends. What did frustrate them was the Chinese’s refusal to buy anything. They wouldn’t buy anything at all. The Chinese only wanted to sell, sell, sell. And as payment they would accept only bullion, bullion, bullion: silver or gold. Or diamonds: diamonds were good. You get the picture. One Qing emperor explained the reason for this: China had everything good. Europeans had nothing worth coveting. Chinese products were superior to any made in Europe. What then would the Chinese buy?

But the product the traders from the west sought out most voraciously was tea. The British had developed a virtual addiction to this beverage. I use the word addiction advisedly: tea is essentially a drug. Today, its stimulating effect may seem too mild to justify placing it in the same category as crack cocaine, but when you consider tea as an alternative to the other major beverage available to Europeans—alcohol, in some form—you can see why tea took Europe by storm. Tea wakes you up, grog conks you out: it’s that simple. (Coffee was starting to get popular, too, but it didn’t rival tea yet.)

In 1720 the British imported two hundred thousand pounds of tea from China. In 1729, they bought a million pounds. By 1760, their tea imports had risen to three million pounds, by 1790 to nine million. Let me repeat that. Nine. Million. Pounds. That’s a lot of tea, eh? Well, hold on to your hat: by the mid-nineteenth century, Britain’s imports of Chinese tea had jumped to thirty-six million pounds a year. Porcelain had once been packed in tea to prevent breakage; now porcelain was carried in the holds of tea ships, as ballast.

Cash, in this case, meant precious metal. Whoever died with the most bullion was the winner—so went the theory, and the theory certainly held true for individual merchants.

The British government couldn’t simply ban tea because it was getting huge revenues from tariffs on imports, almost 10 percent of which were tea. If tea imports were to drop, government revenues would plummet. Britain had just spent a fortune beating the French in a global world war for possession of the world’s colonies. It needed more money, not less. So the government raised the tariff on tea by 100 percent, which discouraged tea sales and slowed down imports without hurting the government’s bottom line. It did hurt somebody’s bottom line, however. The British East India Company’s life depended on selling tea. What was it to do—simply take a loss and die? No way! To help this most powerful of lobbies, the British government passed laws forcing its American colonists to buy expensive company tea instead of the cheaper tea smuggled in by Dutch freebooters (who, of course, paid no taxes to the British Crown). Famously, this Tea Act irked rebellious colonial Americans to such an extent that, one night, a group of anonymous radicals sneaked onto an EEK ship and dumped the modern equivalent of a million dollars’ worth of tea into the harbor. The British government struck back with punitive laws, which fed a gathering storm, the storm that burst out finally as the American Revolution. So yes, the policies of China’s Qing government did contribute to the birth of the United States. Thank you for asking. The two were connected as two ends of the same long causal chain.

CHAPTER 21 Middle World Enmeshed

The Europeans were private businessmen, and private enterprise had a different status in their homelands than it did here in the Muslim world. In Europe, getting rich was a way to have political clout. In the Muslim world, having political clout was a way to get rich

PART VI The Singularity Has Three Sides

CHAPTER 29 Digital Era

They could carry out friendships more and more through e-mail and social media, watch movies on their cell phones alone in their rooms, derive their income from work done online, calculate and file their taxes from their desks, buy and sell securities and thus get rich or go broke without ever moving from their chair.

But here’s the thing. A program that successfully predicts the market will trigger the buying and selling of certain securities today. That buying and selling will affect the markets of tomorrow. Software programs built to predict future market trends will have to take themselves into account. They will have to observe themselves observing the world, predict their own reactions, and then factor those reactions into their predictions. Phew! If that’s not self-awareness, I don’t know what is.

A self-aware computer program observing itself observing the world will need access to the Internet so it can seek out data on its own. Anyone whose computers acquire data on their own will outcompete anyone whose computers only know what their (human) keeper tells them. Computers with untrammeled access to the Internet will have access to self-correcting software that lets a processing device learn from experience and rewrite its own code to incorporate what it has learned. An interconnected network of all the computers on Earth, capable of observing itself observing the world, learning from experience and rewriting its own code—that sounds like a recursive process. It might, like a bell tone in an echo chamber, accelerate exponentially. Somewhere along the way, the single, worldwide, networked, intention-motivated, processing consciousness might become a million times smarter than the smartest human overnight. With robots as its limbs, it will be way stronger too.

I myself am not a convert. The singularity cult cheerfully assumes that when the artificial superintelligence comes into being, it’s whole purpose will be to serve the needs of humans. They picture themselves as immortal children, laughing, playing, eating, lolling. The way it looks to me, however, if the singularity were to happen today, only the rich would live forever. The poor would straggle on in diminishing numbers, surviving for a while because the immortal rich will want servants but become dispensable once technology has progressed far enough to make robots indistinguishable from humans emotionally, sensually, sexually.

CHAPTER 30 The Environment

Consider those tremendous migrations out of rural areas triggered by industrialism. In 1800, most of us lived in little towns or villages, on farms, or as nomads. Only about 3 percent of the world’s population lived in big cities. By 1960, some 34 percent of us did. Today, it’s over 54 percent, and that number is still rising. If the trend continues, we will someday be a purely urban species, not unlike pigeons, rats, and cockroaches. I’m not trying to insult humans; I love humans. I am one myself. I’m just saying.

Single cities such as Tokyo, Mumbai, or Sao Paulo have more inhabitants than did the entire earth in 3000 BCE.

At least five times in our 5 billion years, some catastrophic event wiped out most of the species then alive. The worst of the mass extinctions occurred about 250 million years ago, when 96 percent of all species vanished. What caused it? Theories abound. Volcanic eruptions, acid rain, and global warming have all been blamed. One theory, however, holds that the trouble began with one certain species becoming too successful. These were deep sea bacteria, which emitted carbon dioxide as a waste product. They proliferated so mightily that they depleted the oceans of oxygen, which set off side effects that gathered ruinous momentum. Whatever the causes may have been, the environment changed rapidly, and most life-forms of the time could not adapt quickly enough.

…million years ago, probably because an asteroid crashed into our planet near present-day Mexico. The blast filled the air with dust, which screened out sunlight, leading many plants to die, which led to the death of animals that lived on those plants, which killed predators that lived on the flesh of those plant eaters, and so on. The biggest creatures, such as dinosaurs, were wiped out first, creating an opening for smaller beasts, including a tiny lemur-like animal no bigger than a squirrel, whose descendants branched and branched, until eventually some of them were primates walking around on two legs. We’ve seen those guys before; we see their descendants now. There’s one right here in my office, using my computer. We’re everywhere.

Every year, for example, the amount of earth covered with concrete increases by an area about the size of Britain.

They’re down to a few hundred thousand now—not officially endangered yet but headed that way. Hippos, tigers, blue whales, sea otters, snow leopards, gorillas, giant pandas—get ready to say good-bye: all of them are on their way out. In fact, dozens of species wink out every day, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

Unfortunately, the extinction issue isn’t really a popularity contest. The mass disappearance of species sets off chain reactions that might eventually reach critical mass and manifest as a sixth mass extinction.

As robots take over from human workers, however, that equation may be changing. The class once known as the proletariat is shrinking. At the same time, even as industrial production and industrialized agriculture continue apace, a new class of products has entered the social realm, products that exist purely as information, generated by the relentless pursuit of answers to the question: What else can be digitized? Many of these products feature a curious property: at least for the moment, they are cheap or even free. How can an economy of any size continue to operate if it doesn’t need workers and its products are free?

If so, the universal basic income may institutionalize what Swedish writers Alexander Bard and Jan Söderqvist have termed the consumtariat, the information-age analog to the proletariat of the industrial economy: an underclass living in reduced conditions, whose service to the economy will be their contributions to consumption not production.

CHAPTER 31 The Big Picture

We have trouble making decisions as one whole species because we live in a great many different worlds of meaning, and that’s a problem that exists in the realm of language, not technology.

We all live in domes that we don’t normally perceive. We collude to paint the sky on the ceiling, and when we look up, what we see is not a ceiling or a painting. What we see up there is sky.

Most of the people I’ve met think their community of belief embraces dialogue and debate. I’ve seen it with dogmatic Marxists. I’ve seen it with dogmatic Islamists. I’ve seen it with people trapped in the lockbox of political correctness. All insist they’re open to criticism and debate with anyone except clueless losers like those other guys. I once stumbled on an online chat room where two right-wingers, who both revered Hitler, were arguing vociferously about Himmler. I did not take this to mean that the Nazi community encouraged vigorous free debate.

Once a big picture has formed, a dot can vanish here or there, and it doesn’t matter: the picture is still there. A few new dots can drift into the frame: it doesn’t matter. We incorporate the ones that fit and ignore the ones that don’t, and the picture is still there. But if too many dots disappear and too many more drift in, the picture gets blurry. At some point, the addition or subtraction of just a few dots can bring a whole new picture into view. And with that, the meaning of all the dots can change, for now they are nodes in a whole different web of meaning.

Responding too quickly to surface similarities without exploring context can lead to conflicts that both sides experience as incomprehensible. The noble assertion that “people are all really just the same” can morph all too easily into the assumption that “people are all just like me.” Context is all.

Kuhn was specifically discussing science, but the paradigm shift idea can help decode much that goes on in history too. I’m proposing that every stable society is permeated by a social paradigm that organizes human interactions, gives purpose to people’s lives, and makes most events meaningful. So long as most people subscribe to the paradigm, society can manage its outliers and their ideas.

If, on the other hand, we have to reconfigure our big picture too much, the picture itself grows blurry and loses some of its power to hold ideas (and lives) together. Master narratives need coherence to exist at all. When nothing connects to anything, a society may well be ripe for a paradigm shift. That’s when a few new ideas may come along and—aha! They seem to offer missing links: suddenly a new big picture pops into view! Why, it isn’t a portrait of Lincoln at Appomattox, it’s a picture of the Titanic going down. No wonder nothing made sense before; we were trying to jam all the known facts into the wrong picture. Now that we see what the picture really is, ideas shelved as irrelevant prove to have great significance after all. That splotch that looked like a clumsy rendering of Lincoln’s eye is actually a precise portrayal of the steering wheel on the Titanic. A paradigmatic social change is always going to seem sudden because a paradigm is invisible until it isn’t. When a whole society goes through a pervasive change, it may feel like everyone is changing their mind at once, but it’s actually a social version of the paradigm shift described by Kuhn. We’ve seen it happen many times in history. All the great religions represented paradigm shifts. A discrete set of events took place. They dropped into a pool of incoherence, and suddenly, for a great many people, everything made sense again. Stark social and political examples of social paradigm shifts abound in the last century alone. Consider the sudden metamorphosis of 1930s Germany into a Nazi world. Afterward, horrified Germans tried to represent the momentary triumph of Nazism as a coup: a small clique took power and forced everyone else to behave badly. At the time, however, it certainly looked like a great many Germans simply and rather suddenly bought into the Nazi paradigm—they became Nazis.

People of my generation experienced the 1960s as a mystically sudden and pervasive cultural shift. The world war was receding in memory. Colonies were breaking away from empires. Prosperity was on the rise. All problems seemed soluble. And in that context, a particular set of values emerged around the globe: big and powerful lost prestige, little and feisty acquired cachet. The idea of revolution became glamorous. Identity-based communities formed and demanded liberation, and yet at the same time radical individualism became a thing to celebrate. Some people welcomed this shift, others hated it, but all perceived that something was happening here. In America, in 1969, the word revolution was securely embedded in the paradigm of the sixties. The term Reagan Revolution could have cropped up only as part of a joke. But in 1979, to a majority of Americans, the world narrative touted by Reagan rather suddenly made sense. Even for many people who had burned their draft cards or bras and called police officers pigs, Reagan was describing the real world, and all those shaggy sixties peaceniks blathering about love were out-of-touch children living in a fantasy. It felt like a whole society changed its mind at once. Not everyone celebrated the paradigm shift, but just about everyone felt it happening. People who had been part of the mainstream and who clung to the old paradigm became marginalized outsiders. There are other examples.

A new narrative has the power to draw a clamorous concatenation of people into a single harmonious whole. But that’s not what it always does, alas. A new narrative can also arise out of some smaller complex of ties; it can bind a selected few to a selected few in solidarity against some reviled other, as a way of reinforcing a glad connection to one’s own kind. It can seem like a remedy for the anxiety provoked by the utter meaninglessness of it all. Harmony derived from that sort of solidarity all too often leads to cruelty and horror. History has provided too many examples to enumerate, and there’s no reason to suppose the future will preclude this possibility.

We do seem to be living through one of those periods of growing worldwide incoherence. Old narratives have lost their power, atomized voices are trumpeting new ones (or refurbished versions of old ones), and if someone doesn’t come up with something good, the many moving toward something bad will sow catastrophe. The danger is particularly sharp now because the “society” we’re talking about is not this or that bunch of people but the single intertangled spaghetti of human lives that constitutes all of humanity in this, our global age.

Then again, the danger always seems particular sharp “right now.” I personally don’t remember a time when humanity wasn’t seemingly handcuffed to a runaway train that had lost its brakes and was barreling toward an edge. We may be isolated from one another these days, living in nonoverlapping social bubbles, primed to disagree, unable to adopt a single plan of action as a species, but that’s not necessarily what the future holds.

The prevailing paradigm always tends to feel like the permanent real, discovered at last. The paradigm that feels like the permanent real is what modernity means. Even in unstable times, today is what all of history seems to have been leading up to, which gives the present moment a visceral authority that yesterday can never match. As Dwight D. Eisenhower once put it: “Things are more like they are right now than they have ever been.” But the present doesn’t deserve the authority it enjoys. Something that is always in the process of vanishing has some nerve claiming to be the permanent real. That’s one good reason to ponder history and pay attention to the past. The present, after all, is nothing but the past that will exist in the future.

The goal is not for all of us to become “just the same,” nor to educate “them” so they can join with us, nor to become just like them so we can join their world. The goal is for all of us to find our way around the world with the same map. Only then will all discussions make sense. Only then will all conversations become possible.

Making connections across cultural borders requires that we take context seriously. It’s the only way to glimpse a universe of meaning that we might build with people very different from ourselves. And it isn’t enough to include “them” in one’s own picture as supporting cast. The challenge has always been to get at least an inkling of a perspective other than our own, to be inside another monad. It takes a lot of intellectual craning and neck stretching to picture the world from another center, but there’s no other way to build a world community in which everyone is “us” and nobody is “them.” In a crude way, it’s happened before, but it’s never been achieved perfectly. If it had been, we’d still be living that way. If one whole us ever comes into being, it won’t be living in a world like the one we’re living in now, nor in a world like the one they are living in now, whoever “they” might be. The all-encompassing “we the people” of the future will be living in a world that does not exist—yet. Before it can come into being, someone has to imagine it. And after that, more people have to imagine it. And then lots of us have to believe it’s really there. And then all of us have to behave as though it’s where we’re living now. And then it will be real for as long as the belief endures.