By Bob Spitz, 2005 (992p.)

I admit to being a Beatles fan, but the main reason I decided to read Bob Spitz’s 990-page book was that I figured there would be something to learn about team dynamics, and how it relates to investing. The book is a must-read on that angle alone! What I didn’t expect though, was how the Beatles story would captivate me and get better by the page. Spitz does a fantastic job with facts and story-telling. He succeeds in demonstrating how complicated it was to be a Beatle, and how much those four lads loved their music. Towards the end of their 10-year run as the most famous band ever, they hated each other – and yet, to the last day, they would get together for only one reason – to record great music. It was on April 10, 1970 (link) that Paul McCartney officially announced that the Beatles were done for good, although John claims he quit first. When asked why, Paul answered: “Personal differences, business differences, musical differences, but most of all because I have a better time with my family.”

Bob Spitz is an outstanding biographer. On his website (https://bobspitz.com/) he lists four of his more recent books beside this one. They include Barefoot in Babylon (2014), which tells the story of the Woodstock Music Festival, a Biography of Ronald Reagan (2018), and one of Led Zeppelin (2021). Early in his career, Spitz worked as a manager for Bruce Springsteen and Elton John, so he’s clearly been around the block. Indeed, Spitz has been a writer for a long time. He published a biography of Bob Dylan in 1988, and a book on the New York Knicks 1970 NBA title (1995). The Beatles: The Biography, was my first Spitz book, and it won’t be the last.

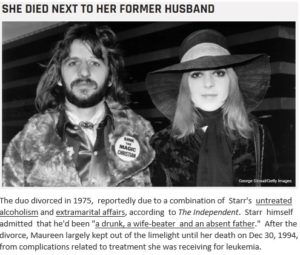

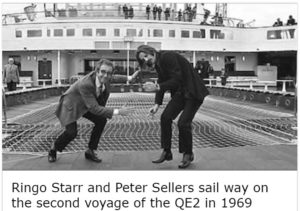

As Spitz pointed out in the End Note, “when the band split, McCartney was all of twenty-nine years old; John and Ringo, thirty; and George, twenty-seven.” That they were young goes a long way in explaining their many mistakes, as do their rocky upbringings, and the zeitgeist of the period. They all took drugs, but it was only John who really lost it because of the drugs, and that only really happened after Yoko introduced John to heroin. Spitz paints John as a selfish and cruel individual, but also a bit of a mad genius, while Paul comes across as a control freak. The book leaves no question that it was Paul who deserves the credit for keeping it together, but then again, Paul and John did more working together than each would ever have done on their own. “Through it all,” Spitz writes, “John and Paul continued to write, with blocks of time devoted to working in their comfort zone: eyeball-to-eyeball.” This was true even when they were already fighting, and it didn’t apply to just John and Paul. When Ringo walked out in 1969 (link), “it didn’t take long for the Beatles to appreciate his absence. A week later a telegram arrived at Ringo’s Mediterranean beach retreat, begging him to return to the studio. Needing no further invitation, he reached Abbey Road on September 9, in time to participate in an uproarious remake of Helter Skelter.” Spitz paints Ringo as a nice guy, but some of my Google searches revealed plenty of dirt. For example, according to this article (link), Ringo’s first wife accused him of being “a drunk, a wife-beater, and an absent father.”

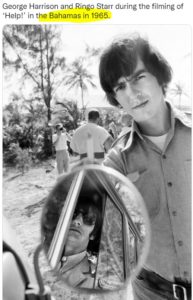

Every Beatles fan has his favorite, and for a long time I thought mine was Paul. He is the brainy Beatle, who according to Spitz, loves to read about all sorts of things, including art and artificial intelligence. But after reading this book, I changed my mind to George – the young one. A mug shot of Harrison taken in Hamburg in Aug 1960, shows just how young he looked when they got started. John and Paul were just 17, but George was 14! When the Beatles landed at JFK airport in early Feb 1964, George was still only 20. Most of the places where they had played to that day would not have let George in, were he not playing with the band. For the next six years since that landing, George would blossom, both spiritually and as an artist. “It was this sense of alienation as much as his interest in music that made George so susceptible to guiding spirits,” explains Spitz. “In the Bahamas during the filming of Help!, he heard the siren song of the sitar and came under the influence of Swami Vishnu- devananda, who introduced him to hatha yoga and Eastern religions. Later in life he would become a vegetarian, consult an astrologer, and devote himself to Transcendental Meditation before embracing traditional Christianity. Like many others who flirted with mysticism, it gave him a sense of authority and confidence.” Unfortunately, Harrison died of cancer in 2001, when he was only 58.

The biggest insight I took away from this book was the importance that purpose played in making the Beatles a huge success. Their purpose was to make music that people liked, and the more people liked what they made, the more focused they became. Shortly after Beatlemania started, the four lads began to dislike their jobs. They were turned off by all the screaming, and took insult (especially John) by the notion that nobody was really listening at the concerts. John started feeling like his whole life was a lie, but he was not alone in being frustrated. Their meteoric rise to fame destroyed their private lives – even though it was precisely what they thought they wanted, and what they had worked so hard for. They craved attention, but they soon began to hate it when they got too much. As Spitz quotes John complaining angrily, “I’ve sold myself to the devil.” They were not the only ones to struggle with fame, but Beatlemania was unlike anything the world had ever seen. People had lost their rockers and young women everywhere were fainting at the site of a Beatle.

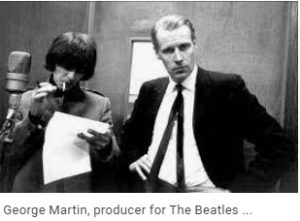

In a paper titled Form Follows Function: Organizational Structure and Investment Results (2016), Mauboussin concludes that “the organization is more important than the individuals within it,” before observing that when it comes to performance, “a team with an odd number of members is at the top of the list. Having three team members allows sufficient diversity to entertain and vet multiple points of views and has a built-in mechanism to break ties.” Some people have called Brian Epstein the Fifth Beatle, while others have bestowed George Martin with that title, but the reality was that there was no odd Beatle. Had Martin gotten his way and they named the band Paul McCartney and the Beatles, there would likely be nothing amazing to write about. To me the number of people matters less than everyone having a unifying purpose. John was crazy enough to say it, but he spoke for their misdirected purpose when he bragged that “the Beatles had become more popular than Jesus.” It wasn’t the money nor the music itself, but the popularity that guided their way, and caused their demise. Viewed from afar and with 50 years of hindsight, it’s amazing they managed to pull it off for as long as they did. Interestingly, some of their best work came out of their most turbulent times.

Regards,

Adriano

PS: I put some extra effort into the Highlighted Excerpts section below.

HIGHLIGHTED EXCERPTS

Note: The earlier chapters focus on the family background and childhood of each Beatle. It’s interesting, but it got better after they started the band.

Chapter 8. The College Band

One pint, however, led to two, then three. “Aside from George,” recalls Hanton, “Paul, John, and I got pretty well drunk.” Slowly but steadily, they got plastered on black velvets— a bottle of Guinness mixed with a half- pint of cider. “By the time we had to go on again, we were totally out of it,” George recalled. Any effort to contain the damage backfired.

Chapter 11. Hit the Road: Jac

Paul remembers being told of the name the next day, along with George, and immediately liking it. “John and Stuart came out of their flat and said, ‘We’ve just thought of a name!’ ” he recalls, smiling. The Beatals. It had the right sound, its reference a dazzling throwback. The name was bluff and cheeky, sturdy; it possessed an easy, buoyant, ornamental quality. The Beatals. Yes, he thought, it would do, it would do nicely.

Not quite everyone. It never even dawned on Williams to include the Beatals on the program. Without a drummer, they wouldn’t stand a chance alongside other major bands. To spare the lads the embarrassment, he made sure they had good seats. In the audience. Punters. Fans. Like everyone else.

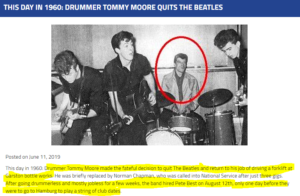

It is not entirely clear who Moore was. Like many musicians who hung around the scene, he was familiar to others by his face, but few had ever heard Tommy actually play. Part of the reason was his age. Already thirty- six, he was well outside the core rock ’n roll demographic— twice Paul’s age— and part of another world as far as performance bands went. He also had a day job, operating a forklift at the Garston bottle works, which made him unfamiliar to the Jac’s daytime crowd. Still, he had all the qualifications: he was small but stocky, with powerful, responsive wrists and impeccable timing. “Tommy Moore was a pro,” says one of the Cassanovas, “what we call a session drummer today. He had played in dance bands, at social clubs. He could put the beat in the right place, and he could play anything.”

Crowning a burst of energy and artifice, arrangements were hastily made. George and Tommy took time off from their jobs, Paul sweet- talked his father into a holiday before the upcoming exams, while John and Stuart simply cut classes. The problem of equipment was similarly solved when they decided to “borrow” the art school P.A. All the pieces fell neatly into place. Suddenly everything seemed possible. They were actually going on the road— a road from which they would never look back. It began with a baby step.

Chapter 13. A Revelation to Behold

But they were records in name only— and not even in their name. As a concession to German slang, in which the word peedles skewed as “tiny dicks”

Chapter 15. A Gigantic Leap of Faith

That was the intricate nature of the band. It put Paul and John at cross- purposes, terrific cross- purposes, that would grow in intensity over the years. Passing was the perfect harmony that marked their songwriting relationship. In its place was a distinction so contrary, a conflict so profound, that the friction it produced built up an armor. Both men schemed aggressively to impose their vision on the Beatles. Always there was Paul’s need to smooth the rough edges and John’s need to rough them up. Somehow, it drove them to fertile middle ground. But the constant compromise was ultimately a debilitating position, and the balance on both sides could not be sustained forever.

Chapter 16. The Road to London

Ron Appleby, who promoted the show, recalled an incident that would soon have far-reaching repercussions. “Brian Epstein decided that everyone who came into the dance before eight [o’clock] would be given a photograph of the Beatles.” It was a nice incentive, although an unusual practice for a Liverpool dance, and it went over in a big way before taking an unforeseen turn. “The girls were ripping up the photograph and sticking the picture of Pete Best onto their jumpers.” No one, especially Pete, had counted on that happening. He was “embarrassed” by the attention, but it wasn’t an isolated incident. “Almost since he joined the band, Pete was the most popular Beatle,” says Bill Harry, expressing a view shared by many early fans. “He was certainly the best-looking among them, and the girls used to go bananas over him.” This phenomenon was nothing new. Best had immense stage presence. Unlike the other Beatles, who mugged shamelessly for the girls, Pete, unsmiling, ignored the crowd, attacking the drums with his long muscular arms, which only heightened his mystique. One can only imagine how much resentment and envy that stirred, especially in Paul, who was sensitive to being upstaged. He’d already gotten bent out of shape by the way Stuart Sutcliffe used to steal the limelight. Now suddenly Pete was crawling up his back. “If one of the others got more applause, Paul would notice and be on him like lightning,” recalls Bob Wooler, whose own behavior did nothing to tone down the jealousy. Wooler had worked out a little rap he delivered at the end of a band’s set to introduce individual musicians. A poster for The Outlaw he’d seen described Jane Russell as being “mean, moody, and magnificent,” which Wooler borrowed and applied to Pete Best. “He was the only Beatle I mentioned by name every time, and it sparked enmity between them—especially with McCartney.”

Chapter 17. Do the Right Thing

Abbey Road wasn’t meant to look like a recording complex, much less a facility like EMI’s other studios at Hayes, which adjoined its record factories. It had originated in 1831 as a nine- bedroom residence, with five reception rooms, servants’ quarters, and a wine cellar, before being converted in 1928 into the world’s first “purpose- [or custom-] built” studio. For all the building’s unpretentiousness, much of the modern technology found in the more imposing high- tech studios was first designed by EMI engineers in one of its boxy, low- ceilinged rooms. The fundamentals of stereo were developed here, as were moving- coil microphones, large- valve tape recorders, and an amusing battery of sound effects that gained industrywide use throughout the war years and beyond. None of that, however, would have impressed the apprehensive Beatles, who were growing increasingly anxious to make their own mark.

The Beatles managed to climb into the coach, but the girls were mobbing Pete and he couldn’t get on.” Everyone on the bus had to wait— and watch. John, Paul, and George watched expressionlessly in the dark. Few friends who observed them realized what this grave demeanor concealed— how, in fact, it was a mask worn to conceal a bitter dissatisfaction. So hard were the lines of their lips and the set of their jaws that they might have been statues for a garden display. Outwardly, their composure never cracked, but inwardly they smoldered as Neil Aspinall extricated his friend from the crowd’s adoring grip. The Beatles never said a word— it was Jim McCartney, of all people, who angrily accosted Pete and accused him of trying to upstage the others— but they had already made up their minds to make sure that it never happened again.

Chapter 18. Starr Time

Of all the drummers in Liverpool, where the pecking order was so clearly established, bands ranked Ringo among the best. And by the summer of 1962, he figured in many of their plans. One band in particular.

It was only ever music, only the band, only the Beatles. There were no other options. This was their life’s work.

Paul’s own deep passion for drumming had never been concealed. He’d long had a trap set at home, which he mastered as he did all the other instruments in the band. And during jam sessions at the Blue Angel, with Gerry Marsden and Wally Shepherd, he “always made for the drums.” Earl Preston’s drummer, Ritchie Galvin, recalled encountering Paul and Pete huddled at the Mandolin Club one afternoon in 1962 after a lunchtime session at the Cavern. “Paul was showing Pete the drum pattern that he wanted on a particular song,” Galvin remembered. “Pete tried to do it, but he didn’t get it.”

The saga of Ringo’s personal history— more like a Dickensian chronicle of misfortune— is one of the erratic tragic chapters in the glittering Beatles legacy. In contrast to the others, who were middle- (John) or working- class (Paul and George), Ringo was “ordinary, poor,” a hardship case. “He was not a barefoot, ragged child,” recalls Marie Maguire Crawford, a neighbor who doubled as his surrogate sister, “but like all of the families who lived in the Dingle, he was part of an ongoing struggle to survive.”

Chapter 19. A Touch of the Barnum & Bailey

Martin, however, was already thinking ahead. The Beatles had put a bug into his ear about image, and he was concerned that the first record should lay it all on the line. “He knew how important it was to establish their identity,” Richards says, “so we kept walking and talked about what to call them— Paul McCartney and the Beatles, or John Lennon and the Beatles.” Martin felt they needed a leader out front, like Cliff and the Shadows. Paul could handle that; he was “the pretty boy” and more outgoing, whereas “John was the down- to- earth type” and the sharp wit. That could also work to the band’s advantage, they decided. It was a tough choice. Paul… John? John… Paul? “It went on like that, back and forth, as we continued along Oxford Street,” Richards says. Nothing emerged from their various proposed scenarios to sway things one way or the other. Each boy had enough star power to carry the group. And yet, a move like that might serve to fracture the beautiful balance they seemed to have found. The band’s personality was pretty much intact— and a very important part of their appeal. There were no apparent power struggles. Besides, Martin mused, maybe the Beatles were right. Maybe this was something new and different that didn’t fall into the same tired mold. “And when we got to the end, we knew it was perfect the way it was.”

Forty years later, Paul McCartney, in nearly every reminiscence, goes out of his way to curse the Northern Songs pact as “a slave deal”— and worse. He believes they were bamboozled out of the rights to their songs and, ultimately, untold millions of dollars, saying: “Dick James’s entire empire was built on our backs.” But at the time, it must have sounded like a sweetheart of an offer. When they were asked if they wanted to read the agreement, John and Paul declined. It called for Northern Songs to acquire Lenmac Enterprises, a holding company set up in April by Brian that owned fifty- nine Lennon- McCartney songs. Under the terms of the agreement, John and Paul were obligated to write only six songs per year for the next four years. During that time, however, they would add an extraordinary hundred new copyrights to the catalogue, each one a classic that would never again be under their control.

Chapter 20. Dead Chuffed

“I think the Beatles shook those crowds up, even scared them a little,” says Kenny Lynch, who watched every set from the cinema wings. “They were so different, so tight, so confident, really playing their hearts out. It was like no experience those kids ever had before. Every girl thought they were singing straight to her, every boy saw himself standing in their place. “It all changed from that night. We took a break a day or two later, before the next leg of the tour, but when we went back out on the road you could tell the whole balance had shifted, because all anyone wanted to hear was the Beatles.”

John was wasted, near collapse, but the others already knew what he was about to find out from a playback: that for all its hairiness, “Twist and Shout” is a masterpiece— imperfect but no less masterful, with all the rough edges exposed to underscore its power. It is raw, explosive. The sound of ravaged lassitude, of everything coming apart, only complements the spirit of a tumultuous live performance.

Mania

Chapter 21. The Jungle Drums

As dreary as the theaters were, their accommodations were often worse— the guesthouses they stayed in run- down, staffed with local help who regarded them as nothing more than riffraff. All- night service stations were the restaurant of choice for most package- tour units, with a heaping portion of starchy beans on toast and chips a safe enough bet to see them through until the next opportunity arose to eat something.

“It was always the same routine: one would play, and the other would be writing down lyrics and chord changes.” They were in their own private world back there, absorbed by the instant gratification of the work and adept at blocking out distractions. [AA comment: Flow].

“John told me that there had never been a day in his life when he didn’t feel he needed some kind of drug,” Dot recalls.

In the first hours of April 8, Cynthia, who had been staying at Aunt Mimi’s house with her friend Phyllis McKenzie, was rushed by ambulance to Sefton General Hospital, where just after 6 A.M. she gave birth to a six- pound, eight- ounce boy. Had it been a girl, she was to be called Julia, after John’s mother. For the birth certificate, however, Cynthia confidently recorded his name as John Charles Julian Lennon. [AA comment: Julian suffered. There is a YouTube interview with him where he says his dad never gave him anything, not even money.]

Sexuality. John was almost as unsparing about gays as he was about cripples and the retarded. “My God, how he ranted about ‘fucking queers’ and ‘fucking fags!’ ” says Bob Wooler, who was privy to many of John’s backstage outbursts. “He was very outspoken, indifferent to anyone’s feelings. He didn’t give a shite about anyone, really— but he was especially intolerant of gays.” But there is every reason to believe that as they became more relaxed, John was drawn further and further into Brian’s guarded confidence. … No doubt John encouraged the direction of the conversation, but Brian did most of the talking, regaling John with details about the life, sometimes with rapturous descriptions of encounters and taboos. In the provocative Spanish sun, Brian became bold enough to behave with John as he might naturally around other gay men, pointing out “all the boys” he found attractive, even daring to act on his desires. “I watched Brian picking up boys,” John recalled, “and I liked playing it a bit faggy— it’s enjoyable.”

Albert Goldman is most emphatic: “[John] and Brian had sex,” he declares in The Lives of John Lennon. Pete Shotton, in his footloose memoir, claims that John told him: “I let [Brian] toss me off.” And in The Love You Make, Peter Brown and his coauthor, Steven Gaines, go so far as to construct an intimate bedroom scene, complete with cartoonish, overheated dialogue, in which “John lay there, tentative and still, and Brian fulfilled the fantasies he was so sure would bring him contentment….” As far as it is known, the issue of homosexuality never surfaced again in John’s life.

Still, it set a dangerous precedent. Brian came away from the vacation brimming with exhilaration, overjoyed that John had opened up to him and poised for something more. He told friends that their time together had been “something to build on” in the months ahead. The other Beatles were aware that something consensual had gone on between John and Brian. In retrospect, Paul referred to it as “the homosexual thing” and suggested that it was John’s way of exercising power over their manager. But if power was part of John’s strategy, he was also exercising it over Paul. More influence with Brian also meant more control of Paul— and ultimately of the Beatles. It was a currency he would collect for the rest of his life.

The Rolling Stones. It was only a month earlier that the Beatles had first laid eyes on them. Following the taping of Thank Your Lucky Stars, an experimental filmmaker and part- time jazz promoter named Giorgio Gomelsky had approached the Beatles in Twickenham, with the intention of making a documentary film about them. Brian, who was already fantasizing about Hollywood, gave him a polite brush- off. Nevertheless, Gomelsky invited the boys to hear a great “full- bodied R& B” band playing at the Crawdaddy Club, which he ran in a room behind the Station Hotel in Richmond, later that night.

Chapter 22. Kings of the Jungle

“There was no longer any question of the Beatles appearing in a club or, indeed, anywhere in direct contact with their public,” writes George Melly in Revolt Into Style. “They had become a four- headed Orpheus. They would have been torn to pieces by the teenage Furies.”

“She Loves You” was finished the next evening, during a rare day off in Liverpool. The boys worked intently in the tiny dining nook at Forthlin Road while Paul’s father sat not five feet away, chain- smoking and watching TV.

“Sometimes, you know, I feel as if there’s nothing I’d like better than to get back to the kind of thing we were doing a year ago,” Paul mused in the midst of the hot summer tour. “Just playing the Cavern and some of the other places around Liverpool. I suppose the rest of the lads feel that way at times, too. You feel as if you’d like to turn back the clock.” If that was even remotely feasible before, all bets were off the moment “She Loves You” hit the airwaves.

Chapter 23. So This Is Beatlemania

Britain’s papers had discovered sex earlier that spring, when they began tracking a colorful rumor that John Profumo, the secretary of state of war, had engaged in a sexual liaison with a young call girl named Christine Keeler. Word had it that he’d met her in 1961 during a weekend social at Cliveden, Lord Astor’s estate, where she was staying with her friend Dr. Stephen Ward. To make matters worse, there were also reports of Keeler’s involvement with a man named Eugene Ivanov, a Russian naval attaché and reported KGB agent, possibly compromising state secrets. At first no paper dared run any part of the story, fearing the harsh slap of England’s libel laws.

NME’s album chart was even more rewarding, listing With the Beatles and Please Please Me as vying for the very top, with three EPs— Twist and Shout, The Beatles Hits, and Beatles No. 1— padding close behind. The dominance was unprecedented. In a single outburst, the Beatles had hijacked the charts.

Chapter 24. Once Upon a Time in America

The New York Times’ TV critic, Jack Gould, dismissed the Beatles as nothing more than “a fad” while giving them credit for a “bemused awareness” that acknowledged their complicity in the clever affair. “Televised Beatlemania,” Gould wrote, “appeared to be a fine mass placebo,” and he summed up the performance itself as a “sedate anticlimax” to all the hype New York had withstood since the Beatles hit town. Visually they are a nightmare: tight, dandified Edwardian beatnik suits and great pudding- bowls of hair. Musically they are a near disaster, guitars and drums slamming out a merciless beat that does away with secondary rhythms, harmony and melody. Their lyrics (punctuated by nutty shouts of yeah, yeah, yeah!) are a catastrophe, a preposterous farrago of Valentine- card romantic sentiments.

When a skeptical reporter speculated in a column as to whether the Beatles’ longevity would last through the month, a colleague pointed out that their ratings for the second Ed Sullivan Show had doubled, and at that rate, there weren’t enough people left in the United States to cover the third appearance.

Chapter 25. Tomorrow Never Knows

As it turned out, it was impossible to put a real dollar value on their worth to Great Britain. No one knew about the $253,000 check from Capitol Records in Brian’s pocket— the Beatles’ share of royalties so far— but it was hot news that the Barclays Bank Review had declared them an “invisible export,” estimating their overseas record sales at something over $ 7 million. But there was no clear picture of what the Beatles actually brought in. Aside from records and performances, merchandising remained a vast gray area. The Seltaeb compact was practically minting money— published reports put it somewhere around $50 million— but who knew how much of that would ever find its way back to the source. Income from the enormous number of bootleg products was impossible to peg.

For the first time in the history of the English charts, British records occupied the top fourteen places. The days of second billing and second- class citizenship for British rock ’n roll seemed over. “With this transition,” wrote pop music historian Greg Shaw, “British rock became real.”

The next morning, Tuesday, February 25— George’s twenty- first birthday— the boys checked into the Abbey Road studio to work on songs for a new album. They could hardly wait to get started. Since the beginning of the year, they had barely played a note that wasn’t drowned out by screams and, as musicians, they had become clearly frustrated by the emptiness of it.

The work itself was more demanding than they’d expected. For one thing, they had to report for costume and makeup at six o’clock in the morning, which meant getting up at five— an ungodly hour for most people but especially for a Beatle. Moreover, they were seriously out of their element. Learning lines was an uphill battle on top of everything else that was going on in their lives. Victor Spinetti, another of their costars, observed how “the lads never touched the script.” In fact, they “frantically” gave it a once- over in the car each morning on their way to the studio, then simply winged it. “You never knew what they were going to say or do.” “We’d make things up because of our being so comfortable with each other,” recalled Ringo. Some real gems came out of their mouths, the same kind of spontaneous witty stuff that dazzled at their press conferences, but for a seasoned film crew it was a hair- raising way to work. To counteract the Beatles’ lack of preparation, Dick Lester kept five cameras running, even after a scene technically ended. “Dick just went on shooting,” Spinetti recalled, “shooting everything…. [H]e just pointed the cameras at them and let them go…. And I just used to keep going…. [W]hen he caught them actually talking amongst themselves, it was just magical.”

Though the review made no strides in the advancement of rock criticism, it gave the record a commendable launch. It also helped distract from the pack of would- be marauders who were pecking at the kingdom walls. Competitors were flooding the market with anything that might capitalize on the Beatles’ success. All along, there had been scores of singles that made no pretensions as to their agenda: “My Boyfriend Got a Beatle Haircut,” “Yes, You Can Hold My Hand,” “Beatle Fever,” “The Beatle Dance,” “The Boy with the Beatle Hair,” “Beatle Mania in the U.S.A.” (by the Liverpools, no less), “We Love You Beatles”— there were too many to keep track of. A start-up label, Top Six, announced that its debut album would provide a full menu of Beatles covers, coincidentally entitled Beatlemania. Another new label, Dial, was banking on a group called the Grasshoppers. Even Decca, at the behest of onetime Beatles producer Mike Smith, recognized the value of ancestry by signing a band called the All- Stars to be led by Pete Best. To their credit, the Beatles wasted not so much as a glance on any of these coattail surfers, their evil eyes trained on more unbenign targets that threatened to cut into their royalties.

It helped defuse the situation temporarily. Still, John wasn’t particularly sympathetic toward the broken-down man and the timing of his visit. “He turned up after I was famous,” complained John, who remained “furious” at Freddie for abandoning him as a child. “He knew where I was all my life— I’d lived in the same house in the same place for most of my childhood, and he knew where.” It may have crushed John to grow up without a father, but it took no effort for him to cut short Freddie’s visit and ultimately order him from Brian’s office. Whatever reasons had rendered his father no longer incommunicado, it was more convenient for John that Freddie remain at large. (Wikipedia for Freddie Lennon).

The women were, in fact, only one small cloudburst in the mammoth typhoon of press that surged through the spring of 1964. Everyone followed the Beatles like a favorite soap opera. Not a day went by that didn’t offer ample stories about their exploits, even if they were only vague speculation. Papers reported on where they were last seen and with whom, how they were dressed, what they had for dinner, when they went home (and with whom). The gloves had come off; all angles were now fair game.

There are several “official” versions of how the title was finally arrived at. What they all agree on is that it occurred during a lunch break at Twickenham Studios, where either Paul remarked to Bud Ornstein— or John to Walter Shenson—“ There was something Ringo said the other day…,” at which point, the two Beatles recounted their drummer’s penchant for “abusing the English language.” “Ringo would always say grammatically incorrect phrases and we’d all laugh,” George recalled. One that sprang easily to mind had popped out at the Heathrow press conference, when Ringo described having his hair cut at the British embassy soiree. “I was just talking, having an interview… and then ‘snip’… Well, what can you say? Tomorrow never knows.” Tomorrow never knows! The Beatles cut wicked glances at one another when that gem fell out. And John promptly wrote it down, to use in one of his stories and, later, songs. There was another malapropism— or “Ringosim,” as John called them— that had already appeared in John’s book, In His Own Write: “He’d had a hard day’s night that day.” One of the boys entertained the lunch gathering with details of its origin, following a grueling late- night gig, but they were already one step ahead of him. “We’ve just got our title!” one of the producers exclaimed.

The next morning on the set, the assistant producer paged Shenson and told him: “John Lennon wants to see you in his dressing room.” The producer went through every imaginable scenario, wondering how he’d respond to the young man’s irritation. “He and Paul were standing there, with their guitars slung over their shoulders,” Shenson recalls. “John fiddled with a matchbook cover on which were scrawled the lyrics to a song—‘ A Hard Day’s Night’— which they played and sang to perfection. This was ten hours after I’d asked for a song.” When they’d finished, John glanced at the producer and said, “Okay, that’s it, right?” It was all Shenson could do to feebly mutter, “Right.” “Good,” John said, “now don’t bother us about songs anymore.”

How George came up with it remains a mystery to this day; he never discussed it, even though the chord has become as identifiable as the song that follows. As it uncoils, there is nothing left to chance. The energy it delivers is explosive, full of fireworks—“ It’s been a haaaard daaaays night…”— and musically as daring, with a vocal track that gathers so much steam that the middle eight (sung by Paul, John explained, “because I couldn’t reach the notes”) comes as almost a relief.

While the Beatles wrapped up work on A Hard Day’s Night, as the movie was now readily being called, Brian left for the Devon coast, where he planned to begin work on an autobiography that had been commissioned by a small London publisher.

Chapter 26. In the Eye of a Hurricane

Over Derek Taylor’s objections, they refused to get off the plane anywhere other than Bangkok, fueling their dark mood with a steady diet of stimulants. “We’d been sitting on the floor, drinking and taking Preludins for about thirty hours [sic],” George recalled. Then, arriving in Kowloon, exhausted and grimy, they were expected to judge the finals of the Miss Hong Kong beauty pageant.

Peter Brown and Brian had spent part of May together, following the feria in Seville among a crowd of aficións that included Ken Tynan and Orson Welles. There, Brown noticed Brian’s growing dependence on pills, amphetamines, that he buffered with excessive quantities of alcohol in an attempt to offset the highs with lows. “It had a disastrous effect on him. It accelerated the mood swings. He was really the sweetest, most sensitive man, but he became belligerent in the blink of an eye. And the worst part was that nobody understood where it came from.”

Art Schreiber, who happened to be passing through the suite, was startled when Paul motioned with his chin and whispered, “I like that one. Can you get her for me?” Answered Schreiber: “Listen, pal, I’m no fucking pimp. I’m a reporter.”

…it was Dylan with whom they would reshape their generation. Paul had discovered him first, buying the Freewheelin’ album before they’d left for Paris at the beginning of the year. That record hit the turntable the moment the Beatles settled into their suite at the George V. “And for the rest of our three weeks in Paris we didn’t stop playing it,” John recalled. In fact, George considered the experience “one of the most memorable things of the trip,” alleviating the irritation of being cooped up in their rooms. One can only imagine the impact that Dylan’s music had on the boys.

It didn’t take long before someone retrieved the communal pillbox from John’s leather bag and Drinamyls and Preludins were offered like after- dinner mints to the edgy guests. The Beatles downed a handful on most nights of the tour as a way of staying up— and up— when their bodies ached for sleep. But Dylan took one look at the assortment of gaily colored pills and shook his head. “How about something a little more organic?” he suggested. “Something green… marijuana.” The Beatles recoiled. They were scotch and Coke men, chain- smokers. Granted, there were the pills, but they served a purpose other than getting stoned. “We’ve never really smoked marijuana before,” Brian interjected, sensing the boys’ immediate discomfort. This, unbeknownst to him, wasn’t entirely true. “We first got marijuana from an older drummer with another group in Liverpool,” George recalled. Besides, an acquaintance had shared a joint with the Beatles at the Star- Club in Hamburg, but it was what Neil called “just the sticks,” which probably meant a deposit of stems mixed with dried oregano or some such filler.

No matter. Rolling “a skinny American joint,” Dylan handed it to John, who gave it a dubious look and passed it on to Ringo, dubbing him “my official taster.” Ringo was no blushing maiden. Without a word, he retreated to a back room sealed with rolled towels— there was a battalion of New York City policemen on a security detail in the hall— and smoked it down to his fingertips. A few minutes later he emerged with a twisted grin plastered on his face. As Paul recounted the experience, “We said, ‘How is it?’ He said, ‘The ceiling’s coming down on me.’ And we went, Wow! Leaped up, ‘God, got to do this!’ So we ran into the back room— first John, then me and George, then Brian.”

The pot had loosened up Brian to a degree that was truly emancipating. He became entranced by his reflection in the mirror. After a moment or two he stood back, then pointed to himself, and blurted out: “Jew!” to everyone’s hilarity. Paul noted how that was the first time Brian had ever referred to himself as a Jew. “It may not seem the least bit significant to anyone else,” he admitted, “but in our circle, it was very liberating.” And a sign to those not red-eyed of Brian’s deep self-loathing.

Chapter 27. Lennon and McCartney to the Rescue

John and Paul had been writing steadily— together and apart— throughout their travels, with about eight songs in good enough shape to record right away. But it had not been a breeze, unlike the previous records. They’d struggled through what John described as “a lousy period,” a time when everything they came up with sounded trite, even flat. There were even hints that the album might have to be put off until the material was up to snuff; but before anyone panicked, they’d finally pounded out a few gems that had the earmarks of their very best work.

Through it all, John and Paul continued to write, with blocks of time devoted to working in their comfort zone: eyeball- to- eyeball. There was always a room available at Abbey Road studios where they could steal a few minutes to bash around ideas. There was also the tiny music salon below the Ashers’ flat, when it wasn’t booked for lessons. Otherwise, Paul ran his new forest green Aston Martin DB out to Kenwood, where John was spending most of his spare time since returning from the States, and they’d spread out in a little mess of an attic room overlooking the garden to “kick things around” for two or three hours.

One day, just as the limo was turning into the driveway, Paul put down his paper and, more out of politeness than real interest, asked the chauffeur how he’d been. The driver gazed in his rearview mirror and shook his head. “Oh, working hard,” he replied with an emphatic huff, “working eight days a week.” A bell went off in Paul’s head. Eight days a week! “It was like a little blessing from the gods,” Paul recalled. No sooner had John answered his door than Paul dropped this little nugget into his hands. “Well, I’ve got the title,” he insisted, and blurted it out. John, normally as competitive as an insurance salesman, knew when to hop on the bus. They practically dashed upstairs and began spitting out lyrics, just “filling it in from the title,” as Paul remembered it. Bam, bam, bam. Much later John dismissed “Eight Days a Week,” saying it “was never a good song,” but at the time they wrote it there was no hesitation as to whether it would fit into their recording plans. An obvious crowd- pleaser, “Eight Days a Week” contains all the drive and spunk of their previous hits, its exuberant spirit punctuated by explosive guitar fanfare, joyous handclaps, and an unforgettable hook—“a typical happy John- and- Paul song,” as Derek Johnson, writing in NME, described it. And each pop hit they offered carved out space for more radical exploration.

There was other carelessness. NEMS’ finances in America were particularly a mess. The proceeds from the last tour had been frozen by the Internal Revenue Service until it was satisfied that proper taxes were paid. That left the Beatles completely out- of- pocket for their five weeks of work. Moreover, during most of the tour Brian had effectively isolated himself from the outside world— there were strings of days when he simply disappeared— to the point that scores of producers and entrepreneurs bearing lucrative proposals, proposals the Beatles should have accepted, were unable to contact him. The number of important deals he let slip through his fingers is scandalous.

It took nearly three years to settle the suit, untangling thirty- nine separate claims against NEMS and a $ 22 million claim for damages, which eventually broke Nicky Byrne and rent the merchandising deal asunder. “The reality is that the Beatles never saw a penny out of the merchandising,” says Nat Weiss, the avuncular divorce lawyer Brian befriended in New York who subsequently took over their American affairs. “Tens of millions of dollars went down the drain because of the way the whole thing was mishandled. Even after the judgment was vacated, you could smell the smoke from the ashes, that’s how badly they had been burned.”

They wanted to make records, not statements. There was too much at stake, too much fever and magic, to antagonize their largely mainstream audience, leaving the extreme rule- breaking to newcomers like the Stones and the Who, both of whom were willing to be outrageous and risk everything for maximum impact.

Most nights, he got stoned in the spacious Gothic toilet. Since returning from the States, John had become more and more devoted to the giddy pleasures of pot, smoking it intermittently throughout the day, from the time he got up until he collapsed from exhaustion. Then he curled up on a couch, brooding and sending out the kind of barbed- wire vibes that discouraged idle chitchat, let alone anything close to intimacy. Guests avoided him, knowing how lethal the combination of sycophants and drugs (and/ or alcohol) could be for John. Of course, the more distant he became, the more the guests ignored him and the harder he had to strike out to draw enough attention. No one was immune. “Everyone who came in was a potential target,” says a frequent guest. When Brian’s favorite, Judy Garland, arrived on Sid Luft’s arm one night, John berated her indiscriminately, implying that she was a hack and introducing her as “Judy Garbage.” On another occasion, feeling “particularly wicked,” he lashed out at an actor’s German girlfriend, blaming her parents for killing 6 million Jews, until the poor girl fled in terror. Other times he was content to pick on Brian, embarrassing him about his sexuality—“ If he pretended to be straight, for instance,” says Bart, “John wouldn’t let him get away with it”— in front of as many people as he could attract. John’s behavior was nothing new. It was the usual outlet for a lifetime of anger, anger at being given up by his mother and her subsequent death, anger at his father for abandoning him without a fair chance, anger at all the parochial teachers who demanded he conform, anger at Brian for tidying up the Beatles’ jagged image (“I’ve sold myself to the devil,” he complained to Tony Sheridan), and anger at trusted friends like Stu Sutcliffe, who died without warning, and now even Paul, who continuously upstaged him.

“Cynthia wanted to settle John down, pipe and slippers” according to Paul— a decision that, to his mind, spelled imminent disaster. “The minute she said that to me I thought, Kiss of Death, I know my mate and that is not what he wants.” For another, they’d been cooped up rather annoyingly in the attic apartment of their new posh home while a team of local contractors gave the living quarters a thorough makeover. It had been hard enough living with Cynthia and Julian in the Emperor’s Gate flat, but in the attic— and miles from nowhere— the situation groaned under the strain. To make matters worse, Cynthia’s mother, Lillian Powell, recently returned from Canada, had moved in while John was on tour and now all of them squeezed into the accommodations like rabbits in a hutch. There wasn’t an ounce of love lost between John and Mrs. Powell, a spiteful, insufferable woman who had never forgiven him for impregnating her daughter and fulminated against her son- in- law every chance she got.

Incredibly, neither Cynthia nor John knew how to drive. They had bought a new Rolls- Royce that sat in the garage until a chauffeur was eventually hired, but even then, with few friends and a young son to take care of, any attempt to steal time away from home was futile. “I would frequently spend weeks of being virtually housebound by duties to child and staff,” Cynthia complained in a memoir. Even when John was around, he usually slept until one or two, then took off for London, rarely coming home until the early hours of the morning, often stoned and drunk. Cynthia had learned to endure his new love of pot, which she viewed as being “relatively harmless” compared with alcohol, but despite the hip and social aspect of getting stoned, it was never something they would share. Alas, marijuana only made Cynthia “sick and sleepy,” further distancing them in their eroding relationship.

Paul, on the other hand, lived between the cracks. Beatlemania was rampant in London, yet for some inexplicable reason he was free to move about with little regard for the usual encroachments. Throughout the end of 1964 and well into the New Year, Paul became a habitué of London nightlife, aggressively cultivating an image as a young man of substance.

Not that they could recall much from the shoot. They had packed ample reserves of pot to get them through the process. The Beatles were so stoned, so distracted, they couldn’t remember lines. Brian’s effort to contain the damage went for naught. Even though, as John revealed, they were “smoking marijuana for breakfast,” mornings seemed to be the only time scenes got completed. By noon they were out of their gourds. “Dick Lester knew that very little would get done after lunch,” Ringo recalled. “In the afternoon, we very seldom got past the first line of the script.”

“Ringo received the most applause, screams, and gasps from the audience.” “I Love Ringo” badges outsold all their other merchandise. The same proved true wherever the Beatles went. “In the States, I know I went over well,” Ringo admitted in a moment of pardonable pride. “It knocked me out to see and hear the kids waving for me. I’d made it as a personality.”

In spite of everything, Ringo was excited to tie the knot. “He’s the marrying kind,” John explained after the news hit the papers, “a sort of family man,” which was true enough. Only a few months earlier, Ringo had told a reporter: “No matter what the consequences, I don’t want to remain single all my life. I want to get married some day and I don’t plan to wait too long about it. I’m 23 now and that can seem pretty old when you look out every night and see an audience full of 13- and 14- year- old girls.”

https://www.grunge.com/284616/the-tragic-death-of-ringo-starrs-first-wife/

https://www.grunge.com/284616/the-tragic-death-of-ringo-starrs-first-wife/

“Ticket to Ride” is hardly gobbledegook, and not at all the self- penned effort for which John eventually took credit. In a hasty reflection, he reduced Paul’s contribution to “the way Ringo played the drums.” However, Paul later argued: “We sat down and wrote it together…. [W] e sat down and worked on that song for a full three- hour songwriting session, and at the end of it all we had all the words, we had the harmonies, and we had all the little bits.”

He [John] was getting tired of hearing Paul described as “the handsome Beatle” or “the cute Beatle,” tired of seeing Paul charm the media, posing as the band’s spokesperson, voicing opinions he didn’t share. Never had John seen anyone turn on the gas like that; throw the spotlight on him and he popped off like a parrot on speed. “He’s a good P.R. man, Paul,” John said, only half seriously. “He’s about the best in the world, probably, he really does a job.” Even as a rock ’n roller, Paul continued to court the kind of establishment approval that offended John. Paul was slick, as slick as they came—“ He could charm the Queen’s profile off a shiny shilling,” says Bob Wooler and not at all kindly— and it stuck in John’s craw. Paul still deferred to John, but skillfully. He knew how to play the angles, which is what it took to humor a cranky hothead like John. Paul could dance archly around his partner’s subtle moods, but on tiptoe, always ready to concede center stage rather than risk confrontation.

To make Paul more comfortable, Martin had the studio lights dimmed to a shade resembling candlelight and moved the other Beatles out of his sight line before retreating with the engineers into the overhead control booth. There was a short last- minute lull while Smith spun dials to get a proper balance. When he finally flashed the thumbs- up, Paul stabbed out his cigarette in an ashtray, cleared his throat, and delivered a “remarkably controlled” take of a ballad that would become the most recorded song of all time. “Yesterday” had been rattling around Paul’s head for nearly two years, since he “woke up one morning with the tune,” tumbled out of bed, and before even washing his face ran through it at the upright piano propped against the wall by the window in his room. What was the source of his inspiration? The question gnawed at him for weeks afterward. Had it come in a dream, as he initially suspected? Was it something he’d heard that his subconscious refused to let go of? Paul hadn’t the foggiest. The chords just kept coming, one after another, falling neatly into place. The melody sounded familiar, to say nothing of cozy, like one of the old standards that his father used to pound out after dinner at Forthlin Road, and while the overall impression it left was “very nice” indeed, Paul convinced himself the tune was “a nick,” something he’d lifted.

“Yesterday” warranted a solo release. Brian, to his credit, wouldn’t hear of it. He was adamant: “No, whatever we do we are not splitting up the Beatles.” But in a way, the bubble was already beginning to burst.

Chapter 28. Into the Cosmic Consciousness

“We’ve had LSD,” John finally revealed to George in a bone-dry voice. The acid had been slipped into their coffee on sugar cubes and might have been an after- dinner cordial, for all George knew. … John was livid. He had not come to dinner to be dosed by a virtual stranger. Mumbling good-byes, they grabbed the girls and bolted, speeding toward the Pickwick, a London nightclub, with the dentist in hot pursuit. For a few minutes everything was fine. They got seated and ordered drinks, squinting in the low light to identify the faces of other musicians who waved to get their attention. “Suddenly I felt the most incredible feeling come over me,” George remembered. “It was something like a very concentrated version of the best feeling I’d ever had in my whole life.” He was overcome with love— hot, feathery, dizzying love. … And none of the Beatles was more receptive to LSD’s spiritual potential than George Harrison. From that very first trip, he felt “a light bulb” go on in his head that blazed the way to enlightenment.

Paul, cautious as ever, wanted nothing to do with it. But Ringo was game, as was Neil, who had Paul’s share, with enough left over for Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, and Peter Fonda. “We were all ripped on LSD,” recalls Fonda, who joined the guests around the pool, while Paul worked in his usual capacity “to keep everything calm and level.”

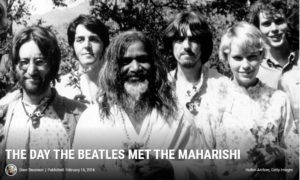

It was this sense of alienation as much as his interest in music that made George so susceptible to guiding spirits. In the Bahamas during the filming of Help!, he heard the siren song of the sitar and came under the influence of Swami Vishnu- devananda, who introduced him to hatha yoga and Eastern religions. Later in life he would become vegetarian, consult an astrologer, and devote himself to Transcendental Meditation before embracing traditional Christianity. Like many others who flirted with mysticism, it gave him a sense of authority and confidence. But with LSD, George stepped out— and into the cosmic consciousness.

Mick Jagger, who, along with Keith Richards, was watching from a seat behind the first- base dugout, was visibly shaken by the crowd’s behavior. “It’s frightening,” he told a companion.

George Martin had been with EMI for fourteen years, ten of them as head of Parlophone, and after a feeble contract negotiation in 1963, he was still earning less than £ 70 a week. All his requests for a commission against sales were rejected out of hand— an outcome made all the more incredible considering his monumental effort in breaking seven or eight NEMS acts, to say nothing of the Beatles. “I was in the studio twenty- four hours a day,” Martin argued. “You know, you don’t [spend] thirty- seven weeks out of fifty- two at number one without working quite hard.” Even so, a commission was unheard- of. Producers and A& R men were company drones, ciphers, lacking any residual perks— not even a car or a negligible Christmas bonus. Martin, who not only brought in tens of millions of pounds, reversing EMI’s flat earnings, but was largely responsible for thrusting the label into the rock ’n roll era, surely deserved at least the same kind of compensation as company sales reps, a reward for his extraordinary success— or so he thought. EMI balked until the summer of 1964, when Martin notified the label that he would not be renewing his contract at the end of its current term. Len Wood attempted to broker a new deal, but each proposal he made was more preposterous, more arrogant— and ultimately more insulting— than the last. When, at their final meeting, Wood, sitting ramrod- stiff and imperious behind a polished yacht- size desk, proposed a deal by which Martin would be forced to reimburse EMI for departmental costs out of his profit, the producer yanked the plug. “Thank you, very much,” George informed him. “I’m leaving.” Martin decided to start an independent production company— a revolutionary concept, “a shock to the recording industry,” NME conceded— that would lease its staff’s services to the labels for a respectable fee against royalties. Not only that, but he was taking a couple of EMI’s young frontline producers, Ron Richards and John Burgess, as well as Decca’s Peter Sullivan, along with him. That gave them— or A.I.R. (Associated Independent Recording), as it was to be called— an artist base that included Adam Faith, Manfred Mann, Cilla Black, Tom Jones, Peter and Gordon, the Hollies, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Matt Monro, Freddy and the Dreamers, Billy J. Kramer, P. J. Proby, Lulu, the Fourmost, and, of course, the Beatles.

Harrison had already become fascinated, if not yet proficient, with the sitar, an Indian lute popularized by Wendy Hanson’s friend Ravi Shankar, and he worked out a subtle arrangement that helped dramatize “Norwegian Wood.” [AA comment: One of my favorites.]

Such experiments were hastened by Martin. “He’d come up with amazing technical things, slowing down the piano and things like that,” John recalled. “They were incredibly inquisitive about the recording process,” Martin recalled. “They wanted to know what they could do that people hadn’t [already] done.” A guideline was immediately established: no idea, however vague or outlandish, was too risky or off- limits. Martin knew better than to dismiss their penchant for experimentation. For every trial concept that crashed and burned, there were four that not only took off but soared.

When it came to musical terminology, however, they couldn’t speak the language. Not only didn’t any of the Beatles have formal training, none could read a note. To stem the lack of communication, they developed a rapport with the eloquent Martin that facilitated discussions about music free of theory- loaded jargon. “Give it some color here,” they might suggest. “Make it punchier.” On one number, “In My Life,” which required an instrumental bridge between the verses, John’s instruction got whittled down to “play it like Bach.” Exchanges like that galvanized Martin, who took up each of their abstract ideas as a challenge. Play it like Bach. That one especially intrigued him. They needed to fill about twelve bars with a piano solo that would lend the song a classical feel. Martin felt he could swing it. Not a pianist by training, he could still manage a fairly decent passage that would approximate “something baroque- sounding,” as John expressed it. “I quickly wrote out a Bach two- part invention [for piano],” he recalled, “ but it was too fast for me to play. So I lowered the speed of the tape to half speed… and then speeded it up [on playback],” an engineering trick that allowed him to simulate an Elizabethan- style harpsichord. Another time, he wove a few sheets of newspaper through the strings of the piano “to make it sound different.” He wrote the middle figure of “Michelle” as well, taking the song’s basic chord structure and inverting it as an instrumental that he played in a duet with John against George’s guitar solo. Martin called these departures “just manipulations of the resources we had at the time,” but that would be akin to playing Hamlet just by putting on the clothes. Resources take resourceful people to manipulate them, and the Beatles, with George Martin’s able assistance, injected originality and daring into the mix that hinted at the great artistic recordings to come.

Mastery

Chapter 29. Just Sort of a Freak Show

Stoned— which they were most of the time in the studio— the experiments became part prank, part innovation. In that kind of dreamy, altered— impractical— state, the possibilities were limitless. Recording became no longer just another way of putting out songs, but a new way of creating them.

“Got to Get You into My Life,” which had begun, according to studio notes, as “a very acoustic number.” Paul had not composed it in a romantic gist, as the lyric might indicate, but ironically, as an ode to drugs. “It was a song about pot actually,” he admitted— not about acid, as John later suspected (Paul hadn’t taken acid yet)— written to a great extent after Bob Dylan turned on the Beatles in New York.

“We were really hard workers… we worked like dogs to get it right.”

Foot pedals for guitars were still a few years off, there were no remote sound- mixing boards, no faders, no monitors. Their new songs, like “Eleanor Rigby” and “Tomorrow Never Knows,” contained crucial sounds that could be made only in the studio. It’d take a pretty substantial horn section to pull off “Got to Get You into My Life.”

A Melody Maker poll reflected the residual impact this had on the Beatles’ popularity by a tabulation showing that 80 percent of respondents were greatly disappointed by the band’s dearth of personal appearances, with only slightly less declaring that Beatlemania had passed its peak. But the Beatles couldn’t have cared less. “Musically, we’re only just starting,” George told a reporter. “We’ve realized for ourselves that as far as recording is concerned most of the things that recording men have said were impossible for 39 years are in fact very possible.”

The Beatles let their hair down for one of the album’s final tracks. On “Yellow Submarine” they gave a blunt comic edge to a children’s song Paul had brought in by layering it with gentle wisecracks and sound effects from their boyhood iconography. Studio Two was in complete disarray as the four Beatles, along with Neil, Mal, and a full battalion of Abbey Road irregulars, ransacked the trap room, a small equipment closet just inside the door, where a trove of noisemaking effects was conveniently stashed. The vast wooden floor was suddenly littered with “chains, ship’s bells, hand bells from wartime, tap dancing mats, whistles, hooters, wind machines, thunderstorm machines”— every oddity they could lay their hands on. A cash register (the one eventually used to ring up Pink Floyd’s “Money”) was dragged out, along with several buckets, a set of bar glasses, even an old metal bath that was promptly filled with water.

Four years: in that brief span they’d collected nineteen number one hits and six gold albums; they’d made two box- office smashes, become virtuosos, and played in front of more people than any other act in the history of show business.

“Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that. I’m right and will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now. I don’t know which will go first— rock ’n roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.” – John Lennon

The concerts were just as remarkable, with none of the hysteria or even screaming that was the hallmark of Beatlemania. “The audience was very subdued,” Ringo recalled. The unsuspecting Beatles found they could actually hear themselves play! “There were one or two screamers,” according to an account, “but for the most part the teenaged boys and girls sat politely in their seats and applauded enthusiastically after each number.” The politeness was due in no small part to the cultural ethos of Japan, as well as the three thousand cops stationed conspicuously in the arena— one for every three kids who’d bought a ticket to the show.

Chapter 30. A Storm in a Teacup

Of all the Beatles, only Paul was inclined to play along. Paul loved the showbiz aspect of Beatlemania, to say nothing of the acclaim. The times he spent on the road— engaging the fans, jawing with reporters, mugging for photographers, and winding up the crowds— were among the highlights of his life. Lionel Bart, who saw him often during this time, called him a born crowd- pleaser and presumed that he’d eventually find his place on mainstream stages like those at the Palladium. “It was clear from the start that show business ran deep in Paul’s veins and he was committed to a lifetime on the stage.” But the other three were disgusted. George especially had had his fill. Ren Grevatt, Melody Maker’s American stringer, had been watching throughout the tour how the whole grind weighed on the Beatles’ personalities. “I’ve noticed that George Harrison is getting deeper and deeper every day and will probably end up being a bald recluse monk,” he observed in an unusually frank column. “He’s trying to figure out life, but don’t let this sound mocking— he is very serious.”

George was fed up with the grim, chaotic life of the Beatles. In discussions with friends, he talked of feeling “wasted” and virtually “imprisoned” by the constraints of Beatlemania. The touring and its effluvia had beat him up, physically and emotionally. “It had been four years of legging around in a screaming mania,” he grumbled. Endless performances—“ about 1,400 live shows,” by George’s count— had left him bored and dispirited. It was all he could do to get up for the thirty-minute appearance.

“We didn’t make a formal announcement that we were going to stop touring,” Ringo recalled. Nevertheless, the matter was settled between them. The August 29 concert in San Francisco would be their last. There would be no more Beatles shows, no more participation in the tumult of Beatlemania. From now on, they would exist solely in the studio as a band that made records.

“We would be Sgt. Pepper’s band, and for the whole of the album we’d pretend to be someone else,” Paul explained. Pretend! Pretend was one of those words that always raised a red flag; the whole thing sounded like a gimmick. Besides, everyone’s head was in a different place.

The skinny, pale boy with big ears and no ambition, the dropout burdened with intellectual insecurity, who used to follow half a block behind John Lennon, had developed into a grimly optimistic, pensive young man clamoring for “the meaning of it all.” LSD had jolted George awake.

… when Brown got back to Chapel Street the next day, he found a note on Brian’s night table, next to an empty vial of Nembutal. Written in Brian’s familiar script, it said: “I can’t deal with this anymore. It’s beyond me, and I just can’t go on.” There was a codicil attached, in which he left his estate to Queenie and his brother, Clive, with other belongings to be distributed among Brown, Geoffrey Ellis, and Nat Weiss. Brian’s desperate act shocked his closest friends. Throughout the tour, his erratic behavior and manic depression had stirred up sympathy and concern. But in the many years they’d known him, even grown accustomed to the emotional jags of his “torturous life,” there was never any indication that he intended to kill himself. Certainly there had been irrational talk, even some low- grade drama. “But none of us, however shortsighted, suspected he was suicidal,” says Nat Weiss.

Certainly, John and Cyn had little more than familiarity left to give each other. There was Julian, of course, but John was hardly an attentive father. He left the parenting to his wife, along with most other household responsibilities. Days went by in which they barely exchanged five words between them, even when living— or rather, coexisting— under the same roof. John was aloof, uncooperative, disappearing into the music room for hours on end or staring hypnotically at the television until he passed out from fatigue. Paul, who seldom saw John during this time, remembered encountering him once in London and asking what he’d been up to. “Well, watching telly, smoking pot,” John replied.

Chapter 31. A Very Freaky Experience

Groups like the Doors and those psychedelic boogie bands that were emerging out of San Francisco put listeners on notice that rock music was growing up. Within the next few years, they would be joined by virtually the entire sixties rock pantheon: Pink Floyd, Janis Joplin, Traffic, Jethro Tull, Sly and the Family Stone, the Band, the Chambers Brothers, Ten Years After, the Jefferson Airplane, Elton John, Credence Clearwater Revival, the Allman Brothers, Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, as well as the entire Motown and Stax/ Volt rosters— all of them swept in in the aftermath of the British invasion and subsequent demise of the Brill Building factory sound. “To those of us making music for a living,” said Pete Townshend, “it seemed like, finally, rock ’n roll had found a perfect groove.” Pop playlists began mixing more progressive “album cuts” with singles, so that songs such as “Windy,” “Happy Together,” and “Somethin’ Stupid” were programmed with “For What It’s Worth” and “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”

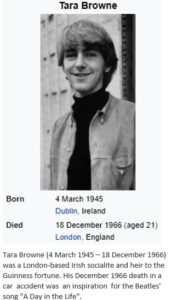

The lyric came, he maintained, during a stretch at the piano, with the January 17 edition of the Daily Mail propped open on the music stand in front of him. “I noticed two stories,” he explained. “One was about the Guinness heir”— Tara Browne, a friend of Paul’s—“ who killed himself in a car. That was the main headline story…. On the next page was a story about four thousand potholes in the streets of Blackburn, Lancashire, that needed to be filled.” Paul’s contribution, he said, was “the beautiful little lick ‘I’d love to turn you on’ ” that had been “floating around” unused.

It had become such an issue that late in 1966, against his better judgment, Paul succumbed to the pressure and dropped some acid in the company of Tara Browne. If he was unwilling to take the drug before, his reaction to it leaned more to ambivalence. Overall, he found it quite “spacy,” a “very, very deeply emotional experience,” ranging in sensations from godliness to depression. Most likely, Paul was too uptight to give it a fair ride.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tara_Browne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tara_Browne

In the meantime, they set to work on the title song, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” which Paul wrote, he claimed, “with little or no input from John.”

In the studio, the Beatles’ regimen of drugs was fairly limited, although Paul has reported— quite surprisingly— that “the one hard drug used during the making of Sgt. Pepper was cocaine.” This amounted to a few lines before the sessions: “For Sgt. Pepper I used to have a bit of coke and then smoke some grass to balance it out.”

Somewhere between Abbey Road and Cavendish Avenue, Paul reached a pivotal decision. “I thought, Maybe this is the moment where I should take a trip with [John],” he recalled. Paul had avoided tripping with the other Beatles. He described himself as “a guy who wasn’t keen on getting that weird” because of “a disturbing element to it.” As a matter of fact, the prospect terrified him. He later attributed his abstinence to common sense; Paul had great reserves of self-control and an eye on posterity. Even with pot, which was consumed with relish, he felt the reins of responsibility.

According to Cynthia, she decided to go against her better judgment and drop acid along with everyone else. In her memoir, she de- scribes it as a “paralyzing” experience, during which she sank into a hollow- eyed depression, withdrew to a bedroom on the second floor of the house, and contemplated jumping out the window onto the stone driveway below. Instead of being drawn into her husband’s grateful embrace, John was furious with her for ruining his drug reverie.

Deep down, Paul loved John in the way someone loved an elder brother. He knew all of John’s faults— many of which frustrated Paul’s ambition— but he still looked up to his partner, even courted his attention. John was a loose cannon, but he was the genuine article.

Chapter 32. The Summer of Love

“I still felt every now and then that Brian would come in and say, ‘It’s time to record,’ or ‘Time to do this,’ ” John recalled. “And [now] Paul started doing that: ‘Now we’re going to make a movie. Now we’re going to make a record.’ ” A feeling crept over John that Paul was somehow trying to dominate the Beatles, which, after all, had been his group. Paul had all but taken over the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions. He contributed so many suggestions for the arrangements, and so fast, so fluently, it was all John could do to keep up with him. It angered him that Paul had come up with the mystery tour concept; he grew peevish, jealous. Why hadn’t he thought of it first? And yet, admittedly, John “enjoyed the fish and chip quality of [it],” the idea that they’d go out “with a load of freaks” and make a low- budget, tongue- in- cheek film. And even if he hated the idea, he may have been distracted— or too fucked- up— to resist.

According to a music journalist, “McCartney arrived at the studio with only three chords and the opening line of the lyric:” “Roll up! Roll up!— for the Magical Mystery Tour.” John and Paul had hit on what was, for them, the perfect bit of wordplay: a phrase that fired up listeners with the keen, romantic cry of circus troupes and carnival barkers rolling their riggings into town— and, a phrase that, to any fan with the slightest streak of hipness, served as a veiled invitation to roll up a joint. It was chock- full of feeble “references to drugs and to trips,” Paul recalled.

Obviously, this frustrated Paul, who thrived on the energy crackling in the atmosphere. Even when the Beatles had no commitments, he seldom rested. At the slightest spark, he would flame into action. “We can do this. Then we can do that. And maybe if this falls into place, we can take it there and do…” If the rest of them wanted to get stoned and sleep in front of the telly, that was their problem. Fuck the dopeheads! Paul was bursting at the seams with creative energy, and nothing, absolutely nothing, was going to stand in his path.

During the afternoon photo shoot, Paul deposited himself majestically in an armchair by the fireplace, sipping champagne and dispensing opinions on everything from art to artificial intelligence, a subject he’d just read about in one of the underground journals he devoured.

Chapter 33. From Bad to Worse

After a brief Hindu prayer was intoned, the Maharishi whispered a handpicked mantra in the disciple’s ear, along with advice that he or she was never to share it with anyone. “It has been specially chosen to harmonize with your personal vibration,” he said. Weeks later, after the novelty had worn off, Mal Evans divulged that his mantra was I-ing, at which point everyone discovered they’d been given the same word.

Peter Brown: The last thing Paul wanted that day was to speak with anyone from NEMS, but if there was Beatles business that needed immediate attention, then he was the only one suited to take care of it. As it turned out, however, this was business of the kind that even Paul was incapable of processing. Brian had so looked forward to the weekend “divertissement” that he skipped the Beatles’ send- off to Wales and headed straight for Sussex in his precious Bentley convertible. There were too many last- minute details that required his attention— an alluring dinner menu, drugs, recreation, discreet sleeping arrangements. … “It was some time before we called the police,” Joanne remembered, “because we wanted to make sure that things were okay in the house— that there were no substances for them to find.” They combed through Brian’s study, tidying up this and that, and waited for David Jacobs, Brian’s lawyer, who was already on his way, via fast train, from Brighton. … Brian Epstein was all of thirty- two years old. On a lovely summer night, he finally got the one thing that had always eluded him: eternal peace.

However, when the Beatles entered Studio Two on Tuesday evening, ready to roll, it was evident that John had come up with a killer. “I Am the Walrus” is pure Lennon fantasy, written, he claimed, over the course of two acid trips. The lyric is based on Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter” from Through the Looking- Glass, which John considered “a beautiful poem,” although he pleaded ignorance when it came to the political undertones in the narrative.

“The Fool on the Hill,” by contrast, evolved in a stunningly straightforward way. Written back in March, days before finishing “With a Little Help from My Friends,” Paul drew unknowingly on personal feelings about social hermits like the Maharishi, whom he had not met at the time. “It was this idea of a fool on the hill, a guru in a cave, I was attracted to,” he recalled. Years earlier he’d heard the tale about a recluse in an Italian hill town who had missed World War II, and that may have sparked the title. But one night in Liverpool Paul conjured up the lonely image and wrote what is arguably one of his finest and most beautiful compositions.

Only John made a specific casting request: he insisted on hiring Nat Jackley, an old- style music hall comedian whom he had always admired, as well as a couple of midgets. (“John would always want a midget or two around,” Ringo noted.)

Stigwood needed control, the Beatles craved complete freedom— neither was willing to give an inch. Of course, Brian’s unsecured 70 percent stake in NEMS raised the possibility of a hostile takeover. Such action was never threatened per se, although elements in the heated exchange gave the impression that it might be considered, prompting the Beatles to issue a public statement. “They would be willing to put money into NEMS if there was any question of a takeover from an outsider,” a spokesman told NME. “The Beatles will not withdraw their shares from NEMS. Things will go on just as before.”

Throughout the fall of 1967, while Britain waged an all- out assault on conformity, the Beatles hastened to consolidate their interests. The longtime holding company, Beatles Ltd., was officially renamed Apple Music Ltd., after which seven subsidiaries were formed: Apricot Investments Ltd., Blackberry Investments Ltd., Cornflower Investments Ltd., Daffodil Investments Ltd., Edelweiss Investments Ltd., Foxglove Investments Ltd., and Greengage Investments Ltd., each capitalized with a substantial financial endowment. Money was no problem. “There was an enormous sum of money— well over a million pounds— that had been accumulated by EMI while the new contract was being negotiated,” recalls Peter Brown. “The Beatles received twenty- five percent of that— and that was the money that set up Apple.”

Paul fancied himself a pretty good businessman. … It mirrored their bickering over the music: each of the two Beatles wanted to put his own stamp on the boutique, each suspicious and jealous of the other’s contribution. Unable to take sides in the matter, Shotton struggled, ineffectually, to please both John and Paul. “They needed someone strong, someone like Brian, to say no, and I wasn’t the one who could do it…. I only ever wanted to be friends with them.”

Chapter 34. An Additional Act

The same rules pertained to the music. John and Paul might preview a nascent song they’d just written for Cynthia or Jane, but other than a rare special occasion— like the “All You Need Is Love” broadcast— women were barred. No woman had ever been invited into the studio and, as far as can be determined, none had asked. In Paul’s view, the studio was sacrosanct, the Beatles’ relationship to it like “four miners who go down the pit.”

Of all the plum roles that had come her way, the Subservient Beatles Woman was the only one Jane Asher refused to play. And Jane hated the drug scene. “Jane confided in me enough to say that Paul wanted her to become the little woman at home with the kiddies,” Cynthia wrote. Another reliable observer says Jane had “clearly decided that she was setting her own terms on how she conducted her career.” There were to be no cop-outs, no compromises, no backseats taken to pop stars.