By John Illsley, 2021 (320 p.)

John Illsley was the bass guitarist and one of the founding members of Dire Straits, my favorite band. I like this band so much that even my teenage boys, who aren’t diehard fans, can sing along to their many classic songs that I have played to them since they were babies.

Illsely was one of the founding members of Dire Straits in 1977, with the Knopfler brothers and drummer Pick Withers. While Illsley was not fond of standing out with his base sound (no chord slapping), he played a major role in developing the band’s musical style, as well as in keeping the members together over the years. In 1980 they added keyboardist Alan Clark, who modernized the band’s music and played a big role in the hit albums Making Movies (1980), Love Over Gold (1982), and Brothers in Arms (1985).

Mark’s brother, David, who played rhythm guitar, left the group after fighting with Mark while they were recording Making Movies, and wasn’t even credited in the album. The band members “took a break” in 1988, but reunited a couple of years later to release On Every Street (1991), which was one of my favorites. Both Knopfler and Illsley went on to release solo albums after the break, with Knopfler venturing into country music and even making an appearance on Saturday Night Live in 1990.

Illsley and Knopfler have remained friends and by some accounts, Illsley has repeatedly asked Knopfler over the years to re-form Dire Straits, but to no avail. Towards the end of the book Illsley discloses that with the help of a therapist, he has found inner peace in Hampshire, England, where he lives with his second wife. He also has four children and four grandchildren. Having turned 73 in June, he spends much of his time painting, but also owns a couple of local hotels and a nearby pub called the East End Arms, situated in the New Forest National Park.

As with most books I venture to read, I was able to draw several great lessons on investing from Illsley’s biography, ranging from the importance of the band’s focus and perseverance in its early years, to the critical role that team dynamics played in their success. For example, Illsley recognized early on that his role as a base player was not to stand out, but to serve as a foundation, or the anchor, if you will, for the band. He played this role not only with his instrument, but through how he interacted with the other members.

The Knopfler brothers had their issues, and this took its toll on the band during its early years. Illsley claims that Dave never accepted that it was his brother who ended up with all the attention when it was he who introduced Mark to the group. While I like their early material, there is no denying that the band blossomed after Dave left. That said, Illsley claims that some of Mark’s best material was produced when he was confronting his darkest times. But like other great bands and companies that thrive, Dire Straits was able to evolve and adapt to a changing world. This ability is one of the most important attributes of outstanding organizations and is something we look for in our investments. The magic doesn’t last forever, but when we conclude that it’s gone, we sell. Likewise, when Mark Knopfler decided it was time to end the gig for good, he did so with conviction and has never looked back.

According to Illsley, everyone understood that Mark was a genius and the star of the band. They all looked up to Mark and drew inspiration from his brilliance and creativity. “Without Mark, there was no Dire Straits,” Illsley writes, “but each of us brought something to the collective effort.” Interestingly, or better yet, impressively, Illsley claims that “Mark isn’t crazy about being the center of attention. He’s shy and modest.” Having a super star that is shy and modest wasn’t the only thing that set Dire Straits apart from the bands of the time. They drank the occasional pint and smoked the occasional joint, but by Illsley’s account, “no one had anything like a serious problem with drink or drugs; it was just a case of how we unwound, dulled the post-gig buzz, and the lack of sleep that entailed.” It was an unspoken rule, but one that was never really broken, that there would be no drinking before shows.

So, all told, this was an excellent book that I would recommend, even to those who are not Dire Straits fans. Illsley comes across as a humble and likeable guy who you’d want as a friend and a mentor. The book is well written and has some hilarious stories and passages that were probably unknown to the general public. It was also a quick and easy read, which always helps.

Regards,

Adriano

HIGHLIGHTED EXCERPTS

Chapter 2: Night Flight to Luxembourg

Our parents probably thought the guitar was the instrument of the devil, but they feigned indifference, happy, I guess, that at least we were learning to play an instrument and not smoking cigarettes down by the railway tracks (although we did that as well!). We had a basic chord book and some sheet music and, once I had mastered where to put my fingers, Will showed me some simple chords on his acoustic, starting with the three basic blues ones, E, A, and B. I found it very hard, but I persevered for hour after hour, barely emerging from my room all day in the holidays and at weekends, at first going from E to A, and from A to E, then expanding the repertoire until my fingers hurt and my brain was fried. You have to really want to learn to play the guitar, or any instrument. It’s why there are so many barely used guitars lying around in the world’s bedrooms, attics, and basements. It takes endless practice to break through and get to the stage when it becomes automatic and you’re not thinking about it, just feeling it.

The Rosetti Lucky Seven was a very crude instrument, but it was probably a good thing that I had to learn the craft the hard way. (Both Keith Richards and George Harrison also learned to play on a Rosetti and, for that reason alone, it deserves an honorable mention in the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame.)

When I upgraded to a half- decent Hofner, I was delighted to discover that not all guitars are born or built equal. It was like getting behind the wheel of a Mercedes after passing my test in a Robin Reliant.

Chapter 3: Banjos, Beatings, and Bass

I was sixteen then, in my third year, and from that day on the art room became my sanctuary, a refuge from the harsher world beyond. It was the day I realized there was always a way out of whatever hell you might find yourself in. There was always sanctuary somewhere, be it in art, music, or the company of a good man. Or woman. “I’ll be here all the time,” Don said. “Come in whenever you like, even if you just want to hang out and chat.” The older I have become, the more I have come to respect John Hedley, but at the time it was very hard to imagine him making the same offer, and I needed no second invitation from Don to indulge in his company and enjoy his outlook on life and art.

Chapter 6: Mr. Knopfler, I Presume?

There was a man lying on the cement floor fast asleep— the promised carpet had never materialized— and his head, propped against the only chair, was at right angles to his body. The guy had an electric guitar across his chest. To one side of him, the giant square ashtray spilled over with a thousand butts; on the other sat a couple of empty bottles of Newcastle Brown Ale. His face, sheet- white, revealed a hint of David. This must have been the brother he had mentioned. He stirred and groaned, and an eyelid unstuck itself. “Cup of tea?” I asked. When I came back, he had cleared up the cigarettes and the beer bottles and I heard him splashing his face in the bathroom. I picked up his guitar, a Gibson Les Paul Junior. Nice. He came back in and I handed the tea to him. He held out his hand and, in a mellow Geordie accent, he said, “Mark, by the way. Mark Knopfler, David’s brother.” “I guessed as much. Heard a lot about you. John— John Illsley. Nice one.” He sat down on the only chair and I perched on the old sofa bed I had found in a builder’s skip a few weeks earlier. We fell into an easy chat about this and that. I took to him at once. There was a natural air and softness about him, and you could see him thinking hard before he answered a question. The conversation drifted toward music and he picked up his Gibson and started playing. He plucked a few strings and twisted the tuning pegs. Then he really started playing, messing around with riffs and snatches of tunes. He had a curious finger- picking style. I had never seen anyone play a guitar like that, but even just fooling around, it was a great sound— a bit country, a bit rock— but fresh and original. Dave was right— his brother could play.

Chapter 7: Punks on the Lawn

I played with the Café Racers now and then, and over a pint after one gig, Mark said, “Why don’t we put a band together?” Not long after, he played me a song he had been working on. He had called it “Sultans of Swing,” the name of an amateur jazz band he and Dave had seen playing in a half- empty Greenwich pub, just a bunch of ageing guys playing music for the sheer love of it. He played it on his newly acquired red Fender Stratocaster through a 1960s Vibrolux amp that I had recently given him. This was the moment when I realized something special was going on. It was just him and his Strat but, not long into it, I became aware I was listening to lyrics and a melody of true craftsmanship and originality. He still has the Strat and the Vibrolux today. Bought for a hundred pounds or so, the guitar is probably worth about £ 30,000 on the open market— and a great deal more on account of its owner.

A week later, we were in the apartment and I was messing around with some reggae sounds on my bass. Mark said, “Hey, that might just work on this song I’ve been toying with since that art exhibition. I’ve called it ‘In the Gallery.’”

There have been a number of stories about how the name Dire Straits came about, but we are in broad agreement that it probably came from a keyboard- playing pal of Pick’s north London roommate Simon Cowe, who was in the band Lindisfarne. We’d agreed to keep rehearsing together and to start hunting down some gigs, so we needed a name. Simon apparently said to Pick, “You’ve never made any money, mate, and you’re always in dire straits. How about that? Dire Straits!”

Punk was in full cry at the time, and I have to confess, apart from a few acts like the Clash and the Sex Pistols, I was no fan.

It made perfect sense. It was angry music, almost anti- music. That was the point of it, wasn’t it? To distort, to pervert, to mock, to do away with harmony and craft, and the anarchy of its outlook was reflected in the tuneless chaos of the “songs.” But they weren’t stupid, these guys, at least not the leading proponents of the movement. Some were putting on an act, and the best of them were consummate performers. Maybe that was because quite a few of them were middle- class lads who had been to art or drama school.

Looking back now, you can see it all more clearly. At the time, we never really thought about our identity. I don’t think we gave much thought to the fashions of the day, so there was no “look.” We didn’t belong to a movement or aspire to be part of one. As a band, we were developing our own style and identity— an attitude that we maintained from then on. Disco and punk were the dominant, happening sounds of the day, and the drift was toward what would become known as “new wave,” with bands like Talking Heads, Elvis Costello and the Attractions, the Police, Squeeze, the Boomtown Rats, and Blondie. We were just doing our own thing in a musical world of our own, and if people liked what we did and there was an appetite for it, then great, so much the better. That was a bonus.

Mark was in a highly creative period and soon we dropped the cover versions and we could fill the show with our own songs.

Chapter 8: Five Hundred Pounds

By the time we made our way up the steps to 2a Grosvenor Avenue, we were in pretty good shape, musically. We didn’t have the time, money, or need to put all our songs down. We just needed the best possible versions of the ones we’d chosen: “Sultans of Swing,” “Wild West End,” “Water of Love,” “Down to the Waterline,” and one by Dave called “Sacred Loving.”

It was a strange experience to hear ourselves coming out of the speakers— it was as if it wasn’t us, but another band. The sound quality was great and the version of “Sultans,” in particular, was excellent. It sounded very pure. There are many people who believe that this is the best recorded version of the song we ever made, and I’m inclined to agree. Who knows? I love it. It’s a strange phenomenon, a song. You can play it a thousand times, but every single version is very slightly different. Again, it all goes back to feel, to the band clicking and syncing in a particular way, plugged into the same mood and vibe. [AA comment: flow]

A bit of a cheer went up as we entered and, as we approached the bar, we got a slap on the back and some broad grins. “Well done, well done. Amazing! Brilliant news.” “What is? What are you on about?” “The radio! Charlie Gillett played ‘Sultans of Swing’ on the radio this morning.” “You’re bloody kidding!” “No, and it gets better. He said ‘Sultans’ was one of the best new songs he’s heard in years and that he was going to play it every Sunday until someone signed you guys up.” After that, as you can imagine, we drank a lot of pints.

Chapter 9: Panic in the Shower

About a week later, the whole band were invited for an evening at a Greek restaurant up in Paddington, not far from Virgin’s offices. It was hilarious— like something out of a film. On arrival, we were ushered into a private room where there were quite a few extremely attractive women, all of whom worked for Virgin and none of whom were overly or formally dressed. A waiter came in with a tray of ready- rolled joints. At dinner, each of us sat next to one of the women and there was a quite a lot of wandering- hand business under the table, and those hands were not ours.

Chapter 10: Off with the Heads

On the subject of hygiene, we were amused and surprised to discover that the [Talking] Heads never cleaned their guitars and only changed their strings when one broke. Even then, they would replace only the broken one, not the whole lot, as was standard practice. Mark and Dave changed theirs every other day.

We had our own instruments, of course, and Mark brought a couple of pedals, but otherwise we shared the equipment with the Heads, walking on and just plugging in. The Heads were very gracious and generous about us using their kit and also in their appreciation of us as their support act, always clapping and slapping our backs as we came off. Remarkably for a support act, we were getting encores from the first gig. Ordinarily, the audience can’t wait to get you off and get into the main act, so it was flattering to be called back on. That could have been awkward with other, less charitable bands than the Heads, but they were genuinely delighted for us. On a couple of occasions, they even asked Mark and me to come on and play “Psycho Killer” with them.

Without Mark, there was no Dire Straits, but each of us brought something to the collective effort.

There are way too many to name, but dozens of great bands and artists have recorded some of the biggest singles and albums of all time at Basing Street: the Stones, Bob Marley, Led Zep, Queen, the Who, Madonna, George Michael . . . the list really does go on and on.

Chapter 11: Wolverhampton Woe to Marquee Magic

So out it came, we held our breath, drum roll and . . . pretty much nothing happened. First time out, “Sultans” barely troubled the charts, peaking at number thirty- seven. The length of it, the version of it— who knows why it failed to make a splash. Of course we were disappointed, but there was the album to come and the tours to promote it, so we got on with preparing for our first UK tour with us as the headline act. Rejection and public indifference are part of the experience for an aspiring band, just as they are in the book world. Both industries have produced countless tales of famous bands and authors who were turned down or ignored for years before breaking through. We were mature enough to understand and weather these harsh facts of life.

Mark had been writing fresh material out on the road for the second album, and we had played a few of the songs at our gigs. It was amazing that he had the time, energy, and inspiration when there was so much going on. I just wanted to go to bed. He was getting close to having a full complement of songs for the second album, which was to be recorded at the end of the year, including “Single- Handed Sailor,” “Lady Writer,” “Where Do You Think You’re Going?,” and “News,” a particular favorite of mine.

Chapter 12: Sessions in the Sun

There are many reasons why it’s hard to sell an album to a record company, and especially in the States, but the main difficulty is that you are not courting and wooing an entire market or audience but just one or two people in an office. If they don’t like it, that’s pretty well the end of the talks, possibly the end of a promising career and the extinction of a great talent.

For example, one time I was in the control room with Barry, who was doing most of the production hard work, and Pick was working on some percussion for the song “Single- Handed Sailor,” about the yachtsman Sir Francis Chichester sailing around the world.

The mixing of an album, very different from recording, is an interesting stage of the process when each element of the music is examined in detail. Mixing is a fine art, but we all had the opportunity to contribute to the end product.

Chapter 14: The Night at the Roxy

In spite of being the heart of the band, and quite literally center stage, Mark isn’t crazy about being the center of attention. He’s shy and modest.

Chapter 15: Into the Arena

Refueling with the usual after- gig refreshments may have given us short- term, nightly relief but, over a long tour, you pay the cumulative price, the compound interest of late-night snacking and pints and any other self- medication of choice. It was around then that I gave up smoking and, although there had always been an unspoken agreement not to drink before a gig, from there on we got a bit smarter about how we unwound afterwards too. No one had anything like a serious problem with drink or drugs; it was just a case of how we unwound, dulled the post- gig buzz, and the lack of sleep that entailed. The main problem was exhaustion and tensions inside the band and with girlfriends, who were always having to compromise. Ed remembers this period as the lowest in the band’s experience.

Mark had been struggling in his private life, and I was astonished that he was able to produce something so beautiful while being so distracted. But, thinking about it afterwards, I realized it was precisely because he had been troubled and anxious that he was able to be so creative. I doubt whether much, if any, great music, art, or literature has ever emerged from the souls of the complacent. A soul in a state of agitation has a better chance of producing great art than one at ease with itself.

Chapter 18: Electric Power

One song that didn’t make it on to the album in the end was “Private Dancer,” mainly because, Mark rightly decided, it should be sung by a woman. The lines “I’m your private dancer, a dancer for money, I’ll do what you want me to do” just didn’t sound right coming from Mark’s mouth! He ended up giving it to Tina Turner— with spectacular results, but more of that later.

I have been privileged to know two great artists well in my lifetime, both great friends: Mark and Brett. Some people you meet have a special way of seeing the world and reinterpret it for the rest of us. Brett was one of those. He did the world great favors with the art he left behind— check it out, it’s mind- blowing— but he did himself no favors in the execution of it. He was tormented by demons. To achieve what he wanted in art, he’d explain, he needed to “nudge it along a bit” or “trick them up” with drink and narcotics. When he was off heroin, he used to throw back three massive whisky and orange juices then hurl himself into his work. He was a very gifted draftsman but felt he needed the boldness he thought stimulants gave him.

Chapter 19: Brothers and Souls

“Brothers in Arms,” inspired by the recent Falklands War, was a slow, powerful, mournful song about the futility of war, embraced ever since by the Armed Forces as an anthem at charity fund- raising events.

I remember one afternoon when we were recording “Money for Nothing.” The “I want my MTV” line at the end was inspired by Mark seeing the Police talking on an ad for MTV and simply saying, “I want my MTV.” He’d mated that with a few notes from Sting’s composition “Don’t Stand So Close to Me.” In the studio, Mark happened to remark, “I wish Sting was here to sing this part.” And someone said, “Well, he is. He’s here on holiday!” So the next morning, warming up, Sting started singing, “I want my MTV,” over and over. And that was it. His work was done.

Chapter 20: Jerusalem Syndrome

All El Al pilots doubled as fighter pilots with the Israeli Defense Force and it was sobering to hear them explain that if they got the call, they’d be scrambling into their cockpits in half an hour on the wrong end of God knows how many beers and cocktails. We hung out with them until about four o’clock in the morning and, as we said goodbye, all of us pretty smashed, we asked them when they were next on duty. Tomorrow, they said, crewing the 11 a.m. flight to Athens. That was our flight! We were a little nervous, hungover ourselves, as we boarded the 747 just seven hours later, but the pilots were as fresh as daisies when they greeted us. They even invited us into the cockpit for the landing . . . which went very smoothly, in spite of the pilots almost certainly being over the limit.

From Greece, we moved on in our massive caravan of tour buses and trucks to the Montreux Festival in Switzerland, where we were reunited with Sting and his new band, which included Omar Hakim on drums. I am not sure he and Terry chatted for too long, but it was great to see him and thank him for his excellent work. A few gigs earlier, Sting told us, just before going on stage, the band had approached him and the management, saying they weren’t going to play unless they were given more money. Sting said, “Fine, no matter, I’ll play by myself.” And he did, just him and his guitar in front of ten thousand people. The band were back on stage the next night.

A little name- dropping, if you’ll excuse me, purely in the interests of historical record, of course, but after the show we were visited backstage by Prince Albert of Monaco and Princesses Stephanie and Caroline. Royalty had found their way into our sweaty dressing room to pay their compliments and I am happy to report that they were charming— though not so charming that Mark would hand over his shirt, which was an unexpected request.

Chapter 21: Live Aid Union

The tour resumed in Tempe, an inner suburb of Phoenix, Arizona, a city that receives only three centimeters of rain a year and where the temperature averages 100 degrees Fahrenheit in September. It was there that I made the mistake of smoking some local grass that was so strong I couldn’t leave my room for six hours.

Crazier still was our experience in New York, as our crew was forced to work under the tyranny of the Teamsters, the incredibly powerful labor union. They took complete control of setting up the three shows in Radio City Music Hall at the start of October, and our brilliant crew were left as mere bystanders and lackeys. It was so absurd that our lot were forbidden from even touching any of the equipment, let alone plugging anything in— heaven forbid— unless or until they were told to do so. They were all experts in their roles, but they had to follow the Teamsters guys around and wait for orders. It was a corrupt racket and they charged so much money that what should have been three lucrative sold- out gigs ended with our hardly breaking even. There was nothing Ed could do about it because they would just refuse to let us play, but it was still a true joy to play Radio City Music Hall, a historic venue inside the Rockefeller Center and home to the Rockettes precision dance company, famous for their kick- lines. It was the same story when we played Madison Square Garden on the penultimate night of the leg, the Teamsters taking most of the cash and bossing everyone around. But we just had to deal with it and, besides, we were playing “The Garden,” one of the greatest venues in the world, “the holy temple of rock ’n’ roll,” as Billy Joel puts it.

We kept the show on the road for so long, going from strength to strength, rather than into a slow decline and collapse, principally because we looked after ourselves. We never went face- down in a heap of coke, never smashed up a bar, never threw a TV from the window, drove a car into a swimming pool, or wheelbarrowed a harem of hookers around our hotel rooms. That may not be very rock ‘n’ roll, but at least it meant we could keep playing it.

Chapter 22: New Worlds

We stayed in George Martin’s beautiful plantation house, waited upon by the lovely house staff.

Bob Dylan, for me the Picasso of music, has always been prepared to take risks. Never bothered by what others might think, he does what he likes.

In spite of being a smoker then, Mark never suffered a chest cold or a sore throat. There are no understudies in a band, so you have to play.

Chapter 23: What Now?

It would take an entire page to list all Mark’s projects in the years that followed. He wrote scores for films such as The Princess Bride and Last Exit to Brooklyn, produced albums for other artists, including Randy Newman’s Land of Dreams, played on others, appeared live . . . He may have had enough of tour buses, but he couldn’t keep away from the music.

I was thirty- seven when the tour finished and I still wanted to be active, to get involved, to engage with the world in a new way. It was just a question of how and what.

Chapter 24: Here We Go Again

As with Brothers in Arms, it was the four of us who came together for the pre- recording session— Mark, Guy, Alan, and myself— and, as last time, there was the same anticipation to hear the new material for the first time.

I have often wondered how Dire Straits’ music might have turned out had Mark played with a completely different set of musicians. It may well have sounded exactly the same, or very close to what’s out there today, but I doubt it.

Mark was only interested in producing the best result. If something wasn’t working, he was the first to say it.

Chapter 25: When the Music Stops

I was only forty- three, fit as a springer spaniel and, unlike many of my peers in the music industry, I had no substance problems or health issues. That much was good. My body was fine. It was just my head that needed some maintenance work, my soul some nourishment.

It was a relief, and therapy of sorts, to discover that the only people more self-centered and demanding than rock musicians are young kids.

It is not to dishonor the good times I had with Pauline and Louise to say that my marriage to Steph has been the best thing to happen to me, not least in its production of two more delightful children, Harry in 1996 and DeeDee in 1998, both of whom, funnily enough, are very musical. James and Jess are both very happily married, to Beth and Moses respectively, and have two children each. So, a lovely wife, four children, and four grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

The Dire Straits phenomenon began after a chance meeting with Mark Knopfler in a council flat in south London. A remarkably gifted songwriter and musician, and one of my oldest friends, he continues to be a constant inspiration and an exciting person to know.

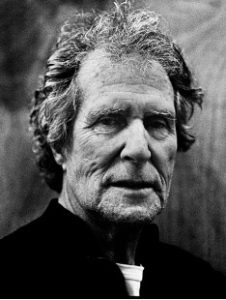

About the Author

About the Author John Illsley rose to fame as the bass guitarist of the critically acclaimed band Dire Straits. With Dire Straits, John has been the recipient of multiple Grammy Awards and a Heritage Award. As one of the founding members (with Mark Knopfler, his brother David and drummer Pick Withers) John played a major role in the development of the Dire Straits sound. When Dire Straits finished touring in 1993, John became involved in the art world. Having carved a reputation for himself as a painter, John had solo exhibitions in London, New York, Sydney, and across Europe. He also cofounded the children’s charity Life Education in 1987, which was recently integrated into Coram, one of the oldest UK charities. John also owns a pub, the East End Arms in the New Forest.