Spikes in oil prices and interest rates have caused shocks to the global economy in the past, and will no doubt do the same in the future. There are many different factors that explain why economic cycles play out, with economic and geopolitical policies, capital movements, and technological breakthroughs competing for prominence in the history books. This time is not different, but neither is it ever the same, since history happens just once.

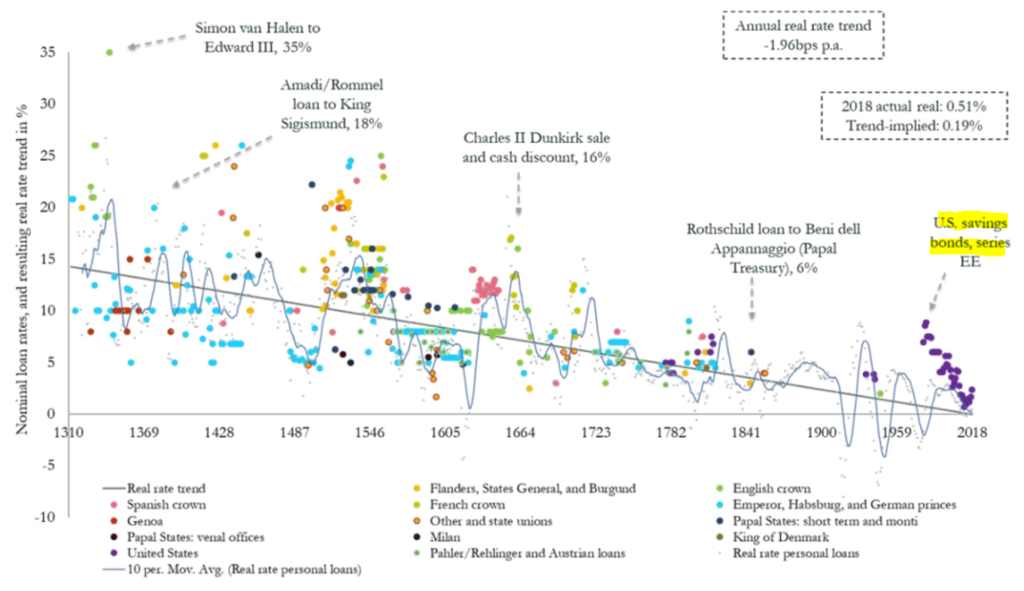

I have endeavored to study the very long term history of markets and the generation of investors that it spawns – not so I can figure it all out (which is not possible) – but so that I can at least have a better feeling for the relevance that macro-economic factors and investment culture have in shaping the trajectory of stock markets. I recently came across a website called Visual Capitalist which provided an annotated picture of the secular decline of interest rates over the last 7 centuries. Note that the highlighted series on the right (for the US), represents a steep decline by historical standards, even though it took 30 years to play out. Most careers on wall street don’t last more than 30 years, but interest rates have been in a secular decline for dozens of generations of investors. Progress has been a feature of the human experience ever since we broke away from other living beings at the dawn of time, and declining interest rates is just one of the ways it plays out.

I think most people who work on Wall Street today were not even alive when rates started to go up in the 1960s. According to Google, the average age of a practicing investment banker is in the 40s. I turn 53 soon and have been on Wall Street for over 24 years, so clearly I was not a part of the great inflation era – although I did grow up in Brazil in the 1980s when hyper-inflation was the norm. The interesting thing is that here we are today.

The history of US 10-year Treasury yields on the Bloomberg shows one of the biggest episodes of mean reversion of our time. There have obviosly been many other episodes in the more distant past, but you can’t pull them up on the Bloomberg. The fact that rates have gone nowhere over the centuries, validates the thesis that they mean revert – but one can’t say the same about stocks over very long stretches of time. What they do instead is that they go up. A 7% long term average return in stocks will turn $1 into $2 in 10 years, $7.61 in 30 years, $868 in 100 years, $653k in 300 years, and $3.7 trillion in 700 years. It’s the main reason there are trillion dollar companies today and none in the past.

Just as an older generation of investors who started in the 1960s and 70s have a hightened awareness (if not an unhealthy obsession) with the mean-reverting tendencies of interest rates, my generation of investors (those who started in the 1990s), have a hightened sensitivity to mean reversion in technology stocks. The Nasdaq bubble can be studied in hindsight, but living through it first hand leaves a much stronger imprint. Cathie Woods is an exception in this respect, since all of the people I know who started funds after the dot-com crash know to guard against disruption hype. Every one has their approach and must make their decisions when the curtain comes down, but passing the buck to the unsuspecting and uninformed is not a good model, and neither is it fair.

Jeremy Grantham has shown in his papers that bubbles tend to overshoot to levels below where they got started. “Bears in bubbles leave no food on the plate,” was a saying I have been known to repeat since at least 2002, when technology stocks were bottoming. I came up with it after reading Grantham’s papers during the dot-com crash.

Grantham (82) was completing his MBA at Harvard in the early 1960s, just as interest rates started to take off. He founded GMO Capital in 1977, when rates were unsustainably high. His approach to investing was developed through a career of watching interest rates rise. According to his Wikipedia page (link): “Grantham’s investment philosophy can be summarised by his commonly used phrase “reversion to the mean.” With this same simple framework, he made a career of calling tops. He was never a stock picker though, and from day one has held the role of Chief Strategist of his firm, much like Cathie Wood was at Jenison for 20 years.

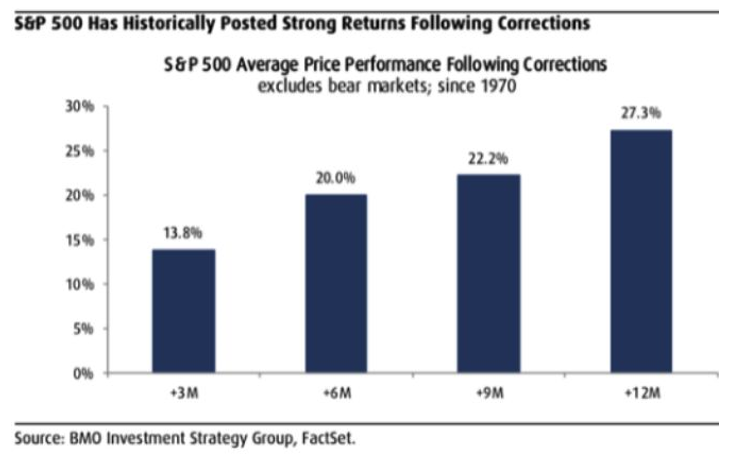

Grantham has often been wrong with his calls, but he never seems to be in doubt. The same argument that Grantham uses to call tops (i.e. mean reversion), other people apply to bottoms. Just this morning one of our analysts shared with the team a chart from a BMO strategy piece that illustrates this point. The caption of the figure reads: All past declines look like an opportunity, all future declines look like a risk.

There are other investors of Grantham’s generation who are still vocal today about the the forces of mean reversion. Howard Marks (75) and Bruce Karsh (66) started Oaktree in 1995 to capitalize on the bargains that macroeconomic mean reversions produce in the distressed debt markets. Marks has written a book on cycle timing, but he admitted that cycles can’t be timed.

Historian Edward Chancellor, who wrote the excellent book, Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation (1999), went to work for Jeremy Grantham in 2008 and has been there since, as far as I know. In 2015 he authored another excellent book called Capital Returns: Investing Through the Capital Cycle: A Money Manager’s Reports. Most of the materials in this book were not written by Chancellor, but he did a fantastic job of organizing and synthesizing the many memos and reports by Marathon Asset management during a period of years. Given Chancellor’s bearish inclinations and his obsession with cycles, he did not emphasize enough how Marathon’s managers changed their views on investing since its founding.

Marathon is a UK hedge fund started in 1998 by Bruce Richards and Louis Hanover to pursue investment strategies in fixed income markets. While they are still known as a credit shop, they evolved into much more of a long-term investor in high-quality growth stocks. One of the memos Chancellor reproduces in his book states that “Marathon’s approach is to look for investment opportunities among both value and growth stocks, as conventionally defined. They come about because the market frequently mistakes the pace at which profitability reverts to the mean. For the value stock, the bet is that profits will rebound more quickly than is expected and for the growth stock, that profits will remain elevated for longer than market expectations.”

In Capital Returns, it is claimed that “Marathon rejects the label value investor, which is generally associated with buying stocks that are cheap based on accounting measures. … Marathon argues that high valuations are often justified for companies protected by deep moats.” Chapter 2, titled Value in Growth, was my favorite because this is where they explained how their mentality evolved regarding the capitalization of mean reversions. Section 2.2 shares a memo written in 2003. I reproduce an abridged version of it below. The memo starts and ends the bolded assertion: Long-term investing works because there is less competition for really valuable bits of information

“There are many ways to describe investment approaches, indeed a consulting industry has emerged whose primary function is to do just that. However, there is one attribute that separates investors better than most, in our opinion, and that is portfolio turnover. Marathon’s portfolios have an average holding period of around five years, a figure which in all likelihood will rise in the coming years as the quality of the companies in the portfolio (as measured by normalized returns on capital and growth potential) has risen, post bubble. We can therefore perhaps be expected to argue vigorously in favour of low turnover investment strategies. While the case for long-term investment has tended to centre around simple mathematical advantages such as reduced (frictional) costs and fewer decisions leading (hopefully) to fewer mistakes, the real advantage to this approach, in our opinion, comes from asking more valuable questions. The short-term investor asks questions in the hope of gleaning clues to near-term outcomes: relating typically to operating margins, earnings per share and revenue trends over the next quarter, for example. Such information is relevant for the briefest period and only has value if it is correct, incremental, and overwhelms other pieces of information. Even when accurate, the value of the information is likely to be modest, say, a few percentage points in performance. In order to build a viable, economically important track record, the short-term investor may need to perform this trick many thousands of times in a career and/or employ large amounts of financial leverage to exploit marginal opportunities. And let’s face it, the competition for such investment snippets is ferocious. This competition is fed by the investment banks. Wall Street relies heavily on promoting client myopia to earn its crust. Why else would Salomon Smith Barney produce a research report which begins “We are focusing on the three month sales momentum model this month”; or Deutsche Bank publish a “Weekly Autos” review? Can there really be much of value to say about industry developments over such limited time frames? Of course not. Even so, we would hate to discourage such research as, from time to time, what the short-term guys are selling can turn out to be wonderful long-term investments. The operative word here is “quick.” The longer one owns the shares, however, the more important the firm’s underlying economics will be to performance results. Long-term investors therefore seek answers with shelf life. What is relevant today may need to be relevant in ten years’ time if the investor is to continue owning the shares. Information with a long shelf life is far more valuable than advance knowledge of next quarter’s earnings. … Even if one has developed the analytical skills to spot the winner, the psychological disposition necessary to own shares for prolonged periods is not easily come by. … Long-term investing works not because it is more difficult, but because there is less competition out there for the really valuable bits of information.”

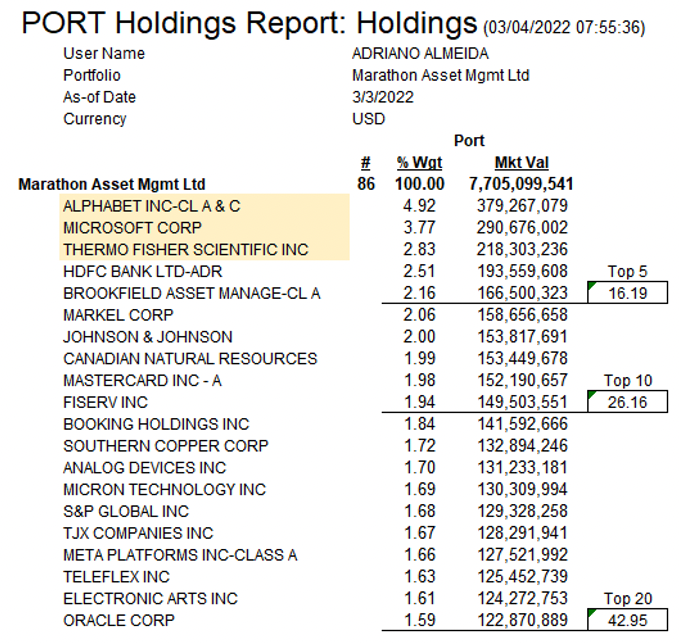

Its interesting that Marathon only came around to this way of thinking over time. Today Marathon manages over $20 billion, with $8b of it captured by Bloomberg through 13F filings. Their portfolio in Bloomberg PORT with year-end 2021 positions and March 3, 2022 closing prices, shows Alphabet as the top position, followed by Microsoft and the lab equipment company Thermo Fisher – three of the highest quality companies I know. To me, Marathon’s position sizes seem small, and the name count of 86 seems way too high. I am not even sure there are 86 companies in the world that fit our standards. But then again, there will always be different ways to get there.

In closing, I could not agree more with Marathon’s assertions that the fewer questions an investor asks, the fewer the mistakes they are likely to make – as long as they are the most valuable questions. At Victori Capital we boil it all down to only three questions, and they are the very same questions we ask for every stock: (1) Why is it an Outstanding Company? (2) Why now? and (3) What are the risks?

Instead of using the imprints of macro cycles to influence my approach, I have built a company on the simple notion that its possible to make dreams come true by investing in outstanding companies over the long-term. The concept itself is simple to understand, yet hard to execute, because of the very cycles that lead most people to default to less optimal approaches.